The Seven Samurai

A film by Akira Kurosawa

By Elliott Long

Akira

Kurosawa’s great film, Seven Samurai, tells a wonderful story and at the

same time reflects the nature of life in post-1945

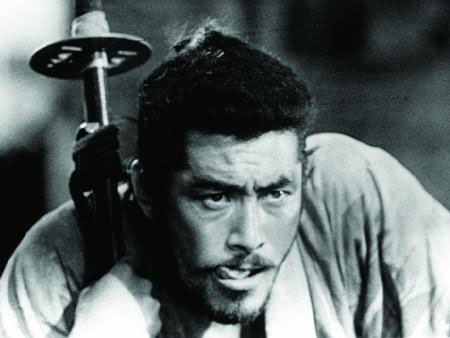

Seven Samurai is a story about a poor farming village community in the 16th century Sengoku era of civil strife and feuding samurai clans. Without the protection of a strong feudal warlord’s samurai, the village is repeatedly raided by a band of outlaws. Its crops are pillaged, its men killed, and women abducted. The villagers decide to hire wandering, masterless samurai (ronin) to protect themselves from the bandits (many of whom are themselves ronin), offering only board and three meals a day as their payment. The first half of the film depicts the plight of the farmers and their difficult search in the nearby provincial town for samurai who are willing to stoop to working for their social inferiors. ‘Find hungry samurai!’ is the wise advice of the village elder; Kambei (played by Takashi Shimura) is the experienced leader chosen, and he recruits five others once the more ambitious willingly turn away. The seventh is Kikuchiyo (played by Toshiro Mifune), a buffoonish, drunken samurai, who follows the men and eventually endears himself to them. From there on, the first half of the film details the bonding of this group, their uneasy relations with the villagers, and the strategies they formulate for fighting the bandits. The remainder of the film is a series of stunningly visualized skirmishes that lead to the final battle. This epic evokes the cultural upheaval brought on by the collapse of Japanese militarism in the 16th century, echoing also the sweeping cultural changes occurring in the aftermath of the Occupation. The plot is deceptively simple yet there had never been a Japanese film in which peasants hired samurai, or an evocation of the social transformation that made such an idea credible. There are seven samurai and together they reflect the ideals and values of a noble class near the point of extinction, whether one is talking about at the samurai in the late 16th century or the old guard who were forced to change after 1945.

The

samurai were the warrior class of lower nobility in feudal

Male friendship is another of the abiding themes of Seven Samurai. The friendship which develops between Gorobei (played by Yoshio Inaba) and Kambei reflects the balm which renders life endurable. It is a friendship which arises spontaneously. Kambei had spotted Gorobei as a kindred spirit even before Gorobei revealed his acute intellect, and before, despite his disclaimer, his sweetness emerges when, casually, he stops to observe a group of street urchins playing. “Try him!” Kambei tells Katsushiro (played by Isao Kimura), his young apprentice. Yet, as the film develops, it becomes a profound connection. Gorobei's decision to help save the village is not motivated by compassion or pity for the farmers. He joins the expedition because, as he tells Kambei, “your character fascinates me.” “The deepest friendship often comes through a chance meeting,” Gorobei believes. Kambei and Shichiroji (played by Daisuke Kato) are renewing an old friendship during which, in many wars, Shichiroji served as Kambei's “right-hand man”. It is a connection leavened by their respective survivals against all odds. Shichiroji remained alive, even after a burning castle tumbled down on him. Between such old friends few words are necessary and among samurai words are particularly superfluous. “Were you terrified?” Kambei inquires. “Not particularly,” Shichiroji answers. “Maybe we die this time,” Kambei notes. At this, Shichiroji just smiles. The samurai immediately develop loyalty, admiration, and love, each for the other, acknowledging and accepting each other's powers and foibles. Seven Samurai chronicles the consolations of male friendship, a theme common to both traditional Japanese culture and the Westerns that influenced Kurosawa as a child.

Relations between the sexes are also played upon by Kurosawa as Kambei’s young apprentice falls for one of the farmers’ daughter named Shino (played by Keiko Tsushima). Fearing such an instance, her father had physically forced her to cut her hair short and dress like a boy before the arrival of the samurai. Still, the young man meets her while out picking flowers and eventually the two have sex (which is not shown but only clearly suggested), which brings the wrath of the father upon the daughter. The two never talk to each other for the rest of the movie; as the three remaining samurai are leaving, the farmer’s daughter passes with only a glance and hurries on to the rice paddies being planted. This kind of relationship would definitely be a shock if it had been depicted in a film before 1945 but now this might seem tame in comparison to the real affairs of Japanese youths today. No longer would arranged marriage or the stern ordering of a parent be the iron fist it once was, the free will of the young has triumphed in spite of it.

Early in the film, Kambei states that selflessness is both pragmatic and the highest good. As the time for the battle with the bandits approaches, Gorobei offers a traditional Japanese perspective, contending that the individual must give way to the group. In the conflict between giri (duty) and ninjo (personal inclination), giri must prevail. ”We'll harvest in groups, not as individuals,” Gorobei explains. “From tomorrow, you will live in groups. You move as a group, not as individuals.” The selflessness which permitted these samurai to agree to help a peasant village must now be inculcated in the farmers themselves. Suddenly, the farmer Mosuke (played by Yoshio Kosugi) and a small group rebel against this order. Because of the nature of the samurais’ defensive plan, he and some other farmer will lose their houses which will be flooded after the harvest and they are horrified. “Let's not risk ourselves to protect others!” Mosuke yells. They break away from the group and rush off. They are only six, however, and Kambei, sword drawn to reveal the urgency of this moment, drives them back to be reincorporated into their units. Later, when Kikuchiyo leaves his post to kill one of the bandit snipers plaguing the defenders, he is reprimanded upon his joyful and victorious return by Kambei for his selfish individual achievement instead of staying at his post. Although Westerners see this type of collective mentally as part and parcel of Japanese (and for that matter Asian) society, when one became a great samurai or a warlord, individualism was praised since it was within their station to act so. Other classes were thought of collectively and with disdain. With 1947 came the imposition of the idea that “all men” were equal; they must all work side by side for the greater good, no matter what their ancestry. Selfish acts in such a time were to be looked down upon now, not class.

The

central hypothesis being “tested” in this social experiment between the samurai

and the peasant class is the question of the possibility of class cooperation

and harmony. The stakes are not only survival, but also social and, by

extension, national peace and prosperity. These stakes have as much to do with

the historical era in which the film is set as they have with the post-war era

of

In fact, this conflict is at the heart of Kikuchiyo’s character. In the film’s most crucial scene, Kikuchiyo presents to the other samurai armor and weaponry that the farmers had kept hidden in a secret cache, expecting them to be pleased at the discovery of these new resources. Instead they are disgusted, knowing that the material would have been stripped from the bodies of dead or murdered samurai after battle. Their anger grows and they even contemplate slaughtering the villagers. In a performance of overwhelming emotional intensity, the hitherto clownish Kikuchiyo lambastes the samurai for their ignorance and hypocrisy, explaining that while the farmers are dull, wicked, murderous, and cowardly, he says that it is the samurai themselves who have made them so, by plundering, burning, raping, and oppressing the peasants on behalf of their warlords. As a victim of that oppression, and one who now aspires to the role of samurai, that is, the role of warrior but in principle also the role of servant and protector of the people, Kikuchiyo’s passion arises from his tragic embodiment of these hierarchical differences between Japan’s people, and by the same token their potential synthesis.

In the

end, the three remaining samurai leave the village while a new generation of

village leaders oversee the planting of the rice; the village elder committing

suicide by deciding to stay in his house which was burned by the bandits and the

other old man getting an arrow in the back from one of them later. One cannot

help but see that this the new Japan, shedding both old military and political

masters, they having served their purpose, for younger and more visionary

persons. There are no tearful goodbyes but only the leaving of the samurai and

the joyous planting of the new crop, safe in knowing that bandits will never

return and that it was the people as a whole that had won the victory. So it has

been for modern

| Home Page | Study Guide| Samurai |