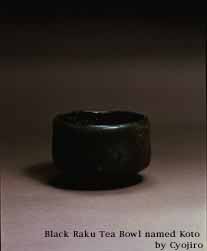

The characteristics of Raku tea bowls as

pioneered by Ch˘jir˘ are their exclusive use of monochrome black or red

glazes - in marked contrast to the brightness of the san cai wares from

which they evolved - and an unique aesthetic which aims at the elimination

of movement, decoration and variation of form. In this Raku wares reflect

more directly than any other kind of ceramic the ideals of wabicha, the

form of tea ceremony based on the aesthetics of wabi advocated by Sen

Rikyu. Central to the philosophy of wabicha were notions of "nothingness"

deriving from Zen Buddhism and the "isness" of Taoism. Raku wares are

hand-formed rather than thrown on the wheel, which makes them very

different from other kinds of Japanese ceramics. Hand-forming increase the

potential for modelling and allows the spirit of the artist to speak

through the finished work with particular directness and intimacy.

Ch˘jir˘, however, through his negation of movement, decoration and

variation of form, went beyond the boundaries of individualistic

expression and elevated the tea bowl into a manifestation of abstract

spirituality. The characteristics of Raku tea bowls as

pioneered by Ch˘jir˘ are their exclusive use of monochrome black or red

glazes - in marked contrast to the brightness of the san cai wares from

which they evolved - and an unique aesthetic which aims at the elimination

of movement, decoration and variation of form. In this Raku wares reflect

more directly than any other kind of ceramic the ideals of wabicha, the

form of tea ceremony based on the aesthetics of wabi advocated by Sen

Rikyu. Central to the philosophy of wabicha were notions of "nothingness"

deriving from Zen Buddhism and the "isness" of Taoism. Raku wares are

hand-formed rather than thrown on the wheel, which makes them very

different from other kinds of Japanese ceramics. Hand-forming increase the

potential for modelling and allows the spirit of the artist to speak

through the finished work with particular directness and intimacy.

Ch˘jir˘, however, through his negation of movement, decoration and

variation of form, went beyond the boundaries of individualistic

expression and elevated the tea bowl into a manifestation of abstract

spirituality.

Ch˘jir˘'s elimination of movement, decoration and

variation of form and his delving beyond the boundaries of individualistic

expression manifested themselves in works of monochromatic silence. To

deliberately negate attempt at any formative expression is, as if

creativity tries to go beyond the act of creation itself, a paradoxical

and extraordinary spiritual endeavour. What was Ch˘jir˘ trying to achieve?

What are we to understand from his attainments? 400 years later, the

issues of spirituality and artistic consciousness addressed by Ch˘jir˘ are

as valid and relevant as ever. |

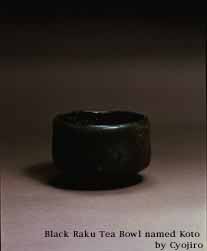

The characteristics of Raku tea bowls as

pioneered by Ch˘jir˘ are their exclusive use of monochrome black or red

glazes - in marked contrast to the brightness of the san cai wares from

which they evolved - and an unique aesthetic which aims at the elimination

of movement, decoration and variation of form. In this Raku wares reflect

more directly than any other kind of ceramic the ideals of wabicha, the

form of tea ceremony based on the aesthetics of wabi advocated by Sen

Rikyu. Central to the philosophy of wabicha were notions of "nothingness"

deriving from Zen Buddhism and the "isness" of Taoism. Raku wares are

hand-formed rather than thrown on the wheel, which makes them very

different from other kinds of Japanese ceramics. Hand-forming increase the

potential for modelling and allows the spirit of the artist to speak

through the finished work with particular directness and intimacy.

Ch˘jir˘, however, through his negation of movement, decoration and

variation of form, went beyond the boundaries of individualistic

expression and elevated the tea bowl into a manifestation of abstract

spirituality.

The characteristics of Raku tea bowls as

pioneered by Ch˘jir˘ are their exclusive use of monochrome black or red

glazes - in marked contrast to the brightness of the san cai wares from

which they evolved - and an unique aesthetic which aims at the elimination

of movement, decoration and variation of form. In this Raku wares reflect

more directly than any other kind of ceramic the ideals of wabicha, the

form of tea ceremony based on the aesthetics of wabi advocated by Sen

Rikyu. Central to the philosophy of wabicha were notions of "nothingness"

deriving from Zen Buddhism and the "isness" of Taoism. Raku wares are

hand-formed rather than thrown on the wheel, which makes them very

different from other kinds of Japanese ceramics. Hand-forming increase the

potential for modelling and allows the spirit of the artist to speak

through the finished work with particular directness and intimacy.

Ch˘jir˘, however, through his negation of movement, decoration and

variation of form, went beyond the boundaries of individualistic

expression and elevated the tea bowl into a manifestation of abstract

spirituality.