|

Robert E.

Haynes |

|

|

Robert E.

Haynes |

|

| 'Joshu Fushimi no Ju Kaneiye' | $NFS |

|

|

| THE ALEXANDER G. MOSLE JOSHU KANEIYE TSUBA OR THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING JOSHU by Robert E. Haynes |

For the better part of the last sixty years I have been searching for this tsuba. By contrast, Kasper Gutman in the "Maltese Falcon" spent only seventeen years pursuing the "bird". My labor of love has now ended as of March 20, 2012, at about 4:20 p.m. At that time I purchased "my" tsuba, which had so long eluded capture, at Bonhams auction number 19696, a day of great joy, and one I shall always remember.

The history of this tsuba is as follows. It first came to light in Japan, circa 1890, when Wada Tsunashiro and Ogura Soemon acquired it from an old noble collection where it had been for many generations. Mr. Ogura was the proprietor of Amiya (the premier emporium for sword fittings in all of Japan) and he was also one of the foremost experts in judging fittings of his day. At about this same time Alexander Georg Mosle (1862-1949) went to Japan to be the representative of Gruson company, a subsidiary of the Krupp family of industries. This was in 1884. Mosle wanted to form a representative collection of Japanese sword fittings. Many of the pieces in that collection came from the Amiya shop. Since Mosle was fluent in Japanese he could do much of his own buying. As he acquired pieces for his collection he made direct contact with Wada, Ogura, and Akiyama Kyusaku (1844-1936), asking them for their advice on his purchases. He also showed parts of his collection to the members of the connoisseurs club, which met regularly to judge fittings, and was attended by the experts mentioned above. All of his fittings that did not pass muster he would eventually eliminate. Thus he formed his highly important collection during the more than twenty years he spent in Japan. He was the only foreigner to assemble a collection with the help and expert advice of all the great authorities living in the Meiji period.

In 1960 at the end of my studies with my sensei Dr. Kazutaro Torigoye, I accompanied him to Tokyo where he introduced me to many private and public collections. During our stay in Tokyo we traveled to the home of Hino Yutaro Sensei, who was the last chief clerk for Ogura Soemon at the Amiya store. Mr. Hino was a small man who was the living image of Fukurokuju. I asked him if he had ever met Mr. Mosle. He said that since he was near the age of Mr. Mosle that he had attended him at the store. He helped him make selections of pieces for his collection. He was surprised at his knowledge and exacting discernment, and thus only showed him the finest pieces they had at the store. Thus it was that he was able to possess the Joshu Kaneie tsuba.

In 1907 Mosle returned to Germany and took with him his collection of 2,240 fittings. In 1909 the collection was exhibited at the Koniglicher Kunstgewerbe-Museum in Berlin. Mosle wrote, in German, a detailed descriptive catalog, that was unillustrated, for this exhibit. In his credits for this catalog were the names of Akiyama, Ogura, Hino, and his other friends in Japan. He also mentioned the names of the European experts of his day, such as, Paul Vautier, Georg Oeder, Gustav Jacoby, and Shinkichi Hara, who created the collection that is now at the Hamburg Museum. All these men had important collections of sword fittings, which they had formed with their extensive knowledge. Many of the pieces in their collections had been purchased from the Amiya store of Ogura where Mr. Hino was chief clerk. The other major collector who bought from Amiya was Dr. Hugo Halberstadt, whose collection of 1,543 fittings is today at the Kunstindutri museum in Copenhagen. In 1914 the German language catalog was expanded, and translated into English and French, with the help of Henri L. Joly (who died in 1919). The First World War was to interrupt any communication between these friends for a number of years. It was not until 1927, when Mosle wrote to Bashford Dean, who was curator of arms and armor at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, to see if they would be interested in acquiring his collection.

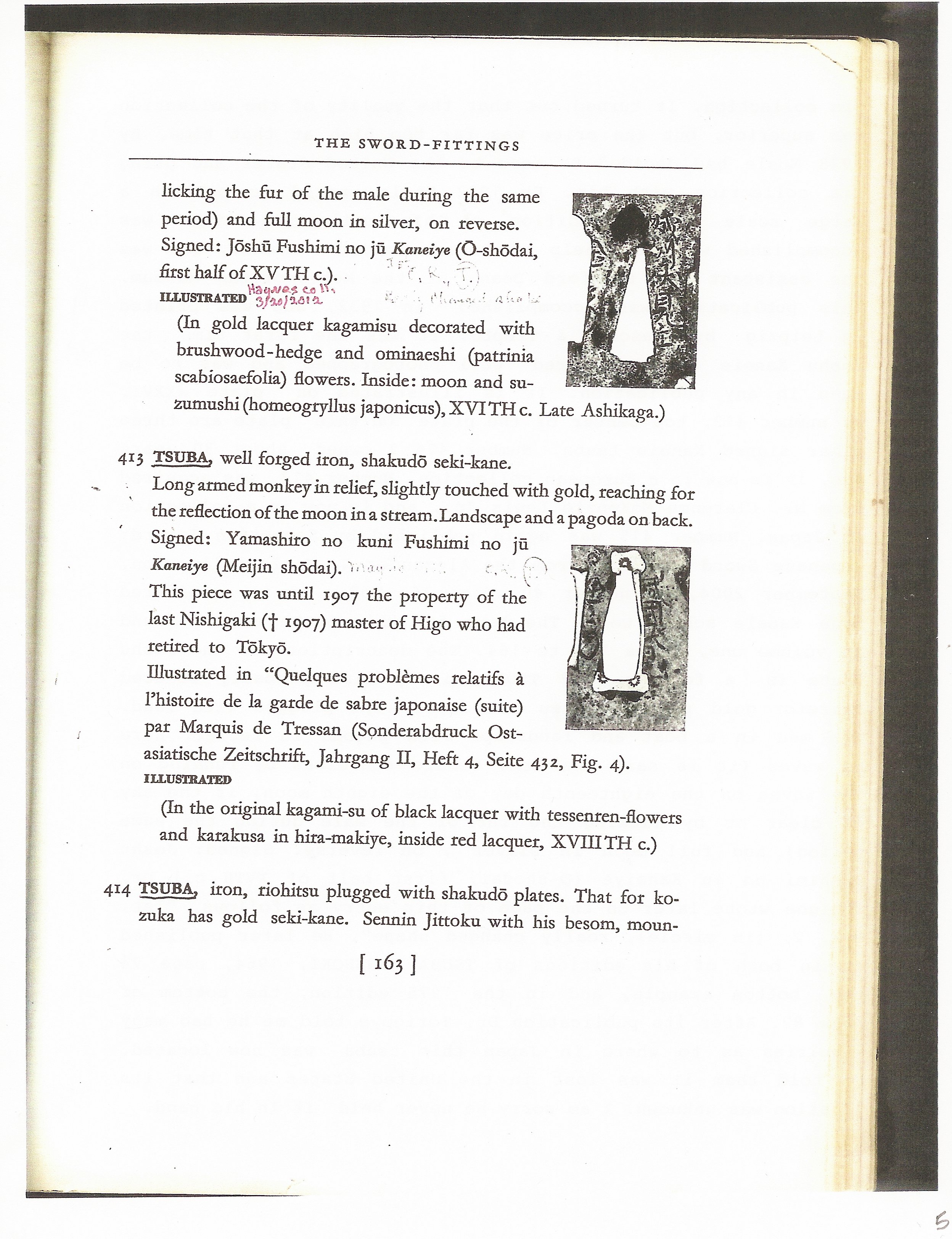

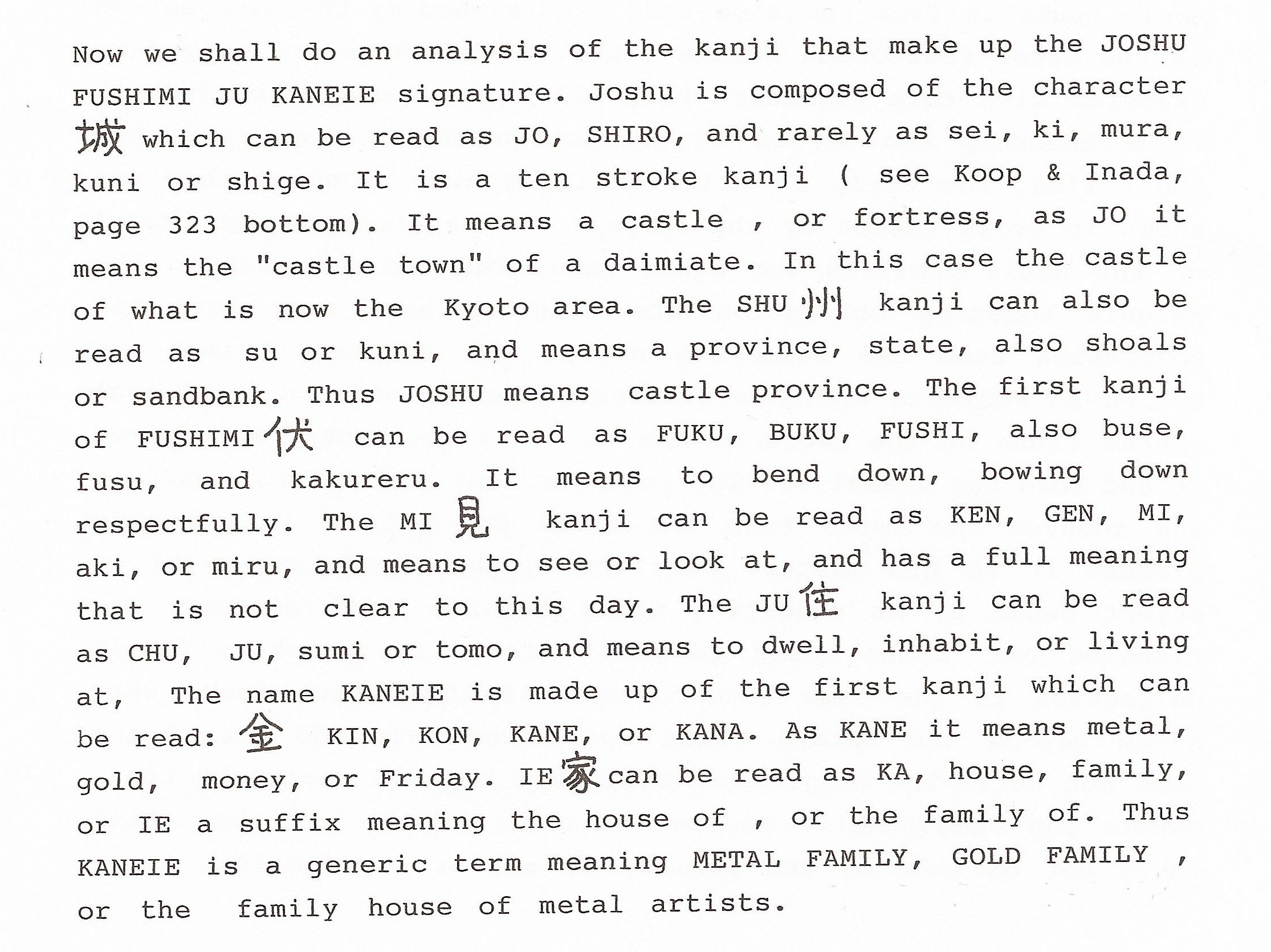

It turned out that the quality of the collection was superior, but the price was far too high at that time. By 1928 Mosle had decided to move to the United States and bring his collection with him. By 1932 Mosle wanted to publish a large scale English edition of his collection. This was accomplished with the help of Robert Hamilton Rucker, who was the assistant to Bashford Dean at the Metropolitan Museum. This publication was accomplished in 1932, and was printed in Leipzig by Poeschel & Trepte. It was the first time the Joshu Kaneie tsuba appeared well photographed and was to be seen in any publication. It is illustrated on plate XXXVI, as number 412, top center of the plate. On this plate are three other signed Kaneie tsuba. Number 414 I owned about 30 years ago, it is now in a European collection. Number 413, was acquired from Mr. Clarence McKenzie Lewis Jr., and is now in a collection in Japan. Number 415 was again published by Sebastian Izzard: Japanese Sword Fittings from the Alexander G. Mosle Collection, September 2004, as number 40, page 36. Today it is considered Saga Kaneie school work. The text for this plate can be found in volume one, pages 162 to 164. The description for the Joshu tsuba is a follows. 412 TSU A, iron, size probably reduced therefor gold rim. Riohitsu cut later, one plugged with lead. Two men in a boat and landscape with pagoda in relief. Hare on waves (it is said that the female conceives by running on the waves on the eighteenth day of the eighth moon, if the sky is clear or by licking the fur of the male during the same period) and full moon in silver , on reverse. Signed: Joshu Fushimi no ju Kaneiye (0-shodai, first half of XVTH c.) Dr. Torigoye wrote later on the page of this entry as follows, "Ist. O.K. T. (in circle), really changed shape". He later published it in both of his editions of TSUBA KANSHOKI, 1964, page 74 the bottom example, and in the 1975 edition, the bottom of page 82. After its publication Dr. Torigoye told me he had many inquiries as to where in Japan this tsuba was now located. He told them it was lost in the United States and that its location was unknown. I am sorry he never held it in his hand.

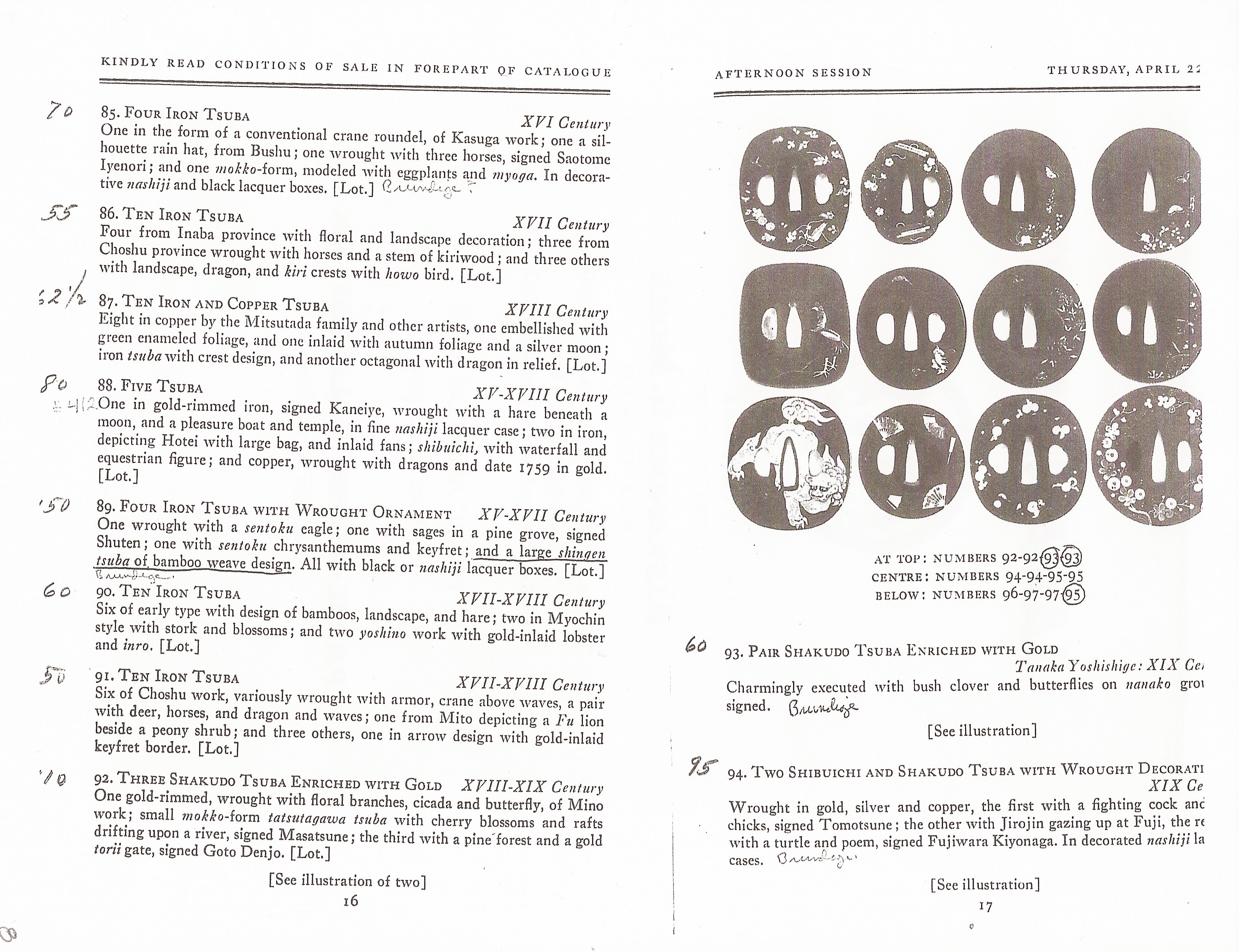

During the 1930s Mosle was still trying to find a home for his collection, either in Europe or America. He traveled back and forth, until in 1939 World War II broke out in Europe, and by 1941 he could no longer return to Germany, as he was 79 and in poor health. At this time he was living in various hotels in New York city, and Washington D.C. By 1946, after the end of the War, he was no longer able to care for himself. Donald A. McCormack of the Riggs National Bank of Washington D.C. was appointed by the courts to handle his affairs. Mosle was to die at Saint Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington D.C. early in 1949. The sale of his collection of fittings had already taken place at the Parke-Bernet Galleries Inc. 30 East 57th Street, New York, on April 22, 1948, at 2 p.m., as sale number 960. There were 205 lots of fittings and the Joshu Kaneie tsuba was in lot 88, one of five tsuba described as follows, "One in gold-rimmed iron, signed Kaneiye, wrought with a hare beneath a moon, and a pleasure boat and temple, in fine nashiji lacquer case; two in iron, depicting Hotei with a large bag, and inlaid fans; shibuichi, with waterfall and equestrian figure; and copper, wrought with dragons and date 1759 in gold". (lot.). There was no illustration of this lot. The five tsuba sold for $80.00! They were bought by Kano Oshima Galleries, 21 East 57th Street, New York City. After I had bought my copy of the Mosle catalog, and had seen the illustration of this tsuba I tried to locate it at once. As I was at this time buying tsuba regularly from Joe Umeo Seo by mail, or when I visited his shop in New York City, I asked him if he new where the Joshu Kaneie was, but he had not bought it and could not remember who had. He suggested that I contact the auction house directly. I wrote to the Parke-Bernet Galleries and they told me that Mr. Oshima had bought the lot. I called his store and was told by Mrs. Oshima that her husband had passed away and she was sorry she could not tell me who had bought the Joshu Kaneie from them as the records were lost. It would seem that it was Clarence McKenzie Lewis Jr. where it remained until it was sold at Bonhams. I was very lucky in one respect, as both John Harding and Dr. Hank Rosin visited Lewis and got many pieces from his collection, but NOT the Joshu Kaneie, which should have been their first choice.

Well there you have the highlights of the history of the Joshu Kaneie tsuba and my quest to obtain it. To whom it will pass in the future is only a question of time. Whom ever it is I hope they love this tsuba as much as I have. If it should return to Japan, so be it, but a good home in a collection in the West would be very fine with me.

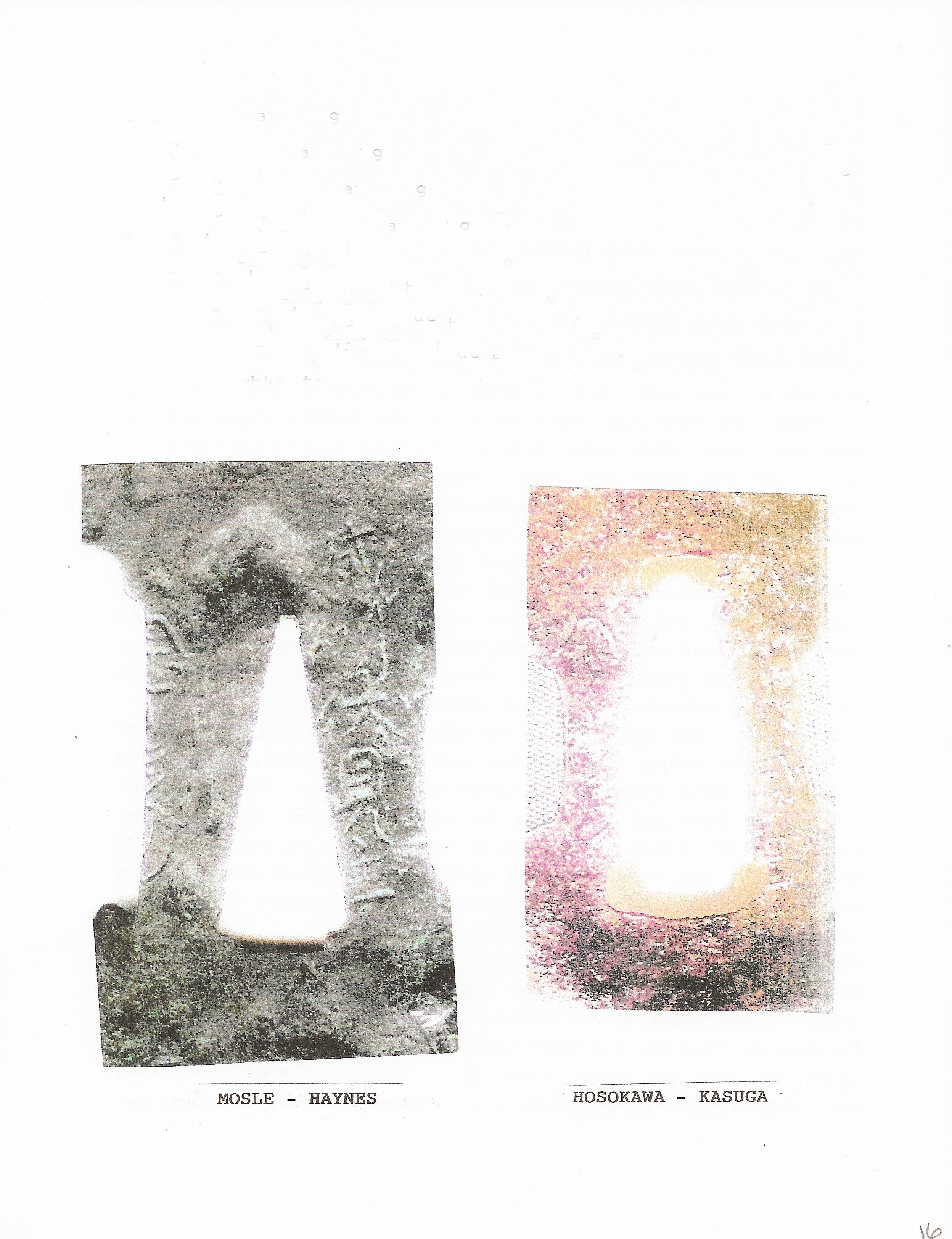

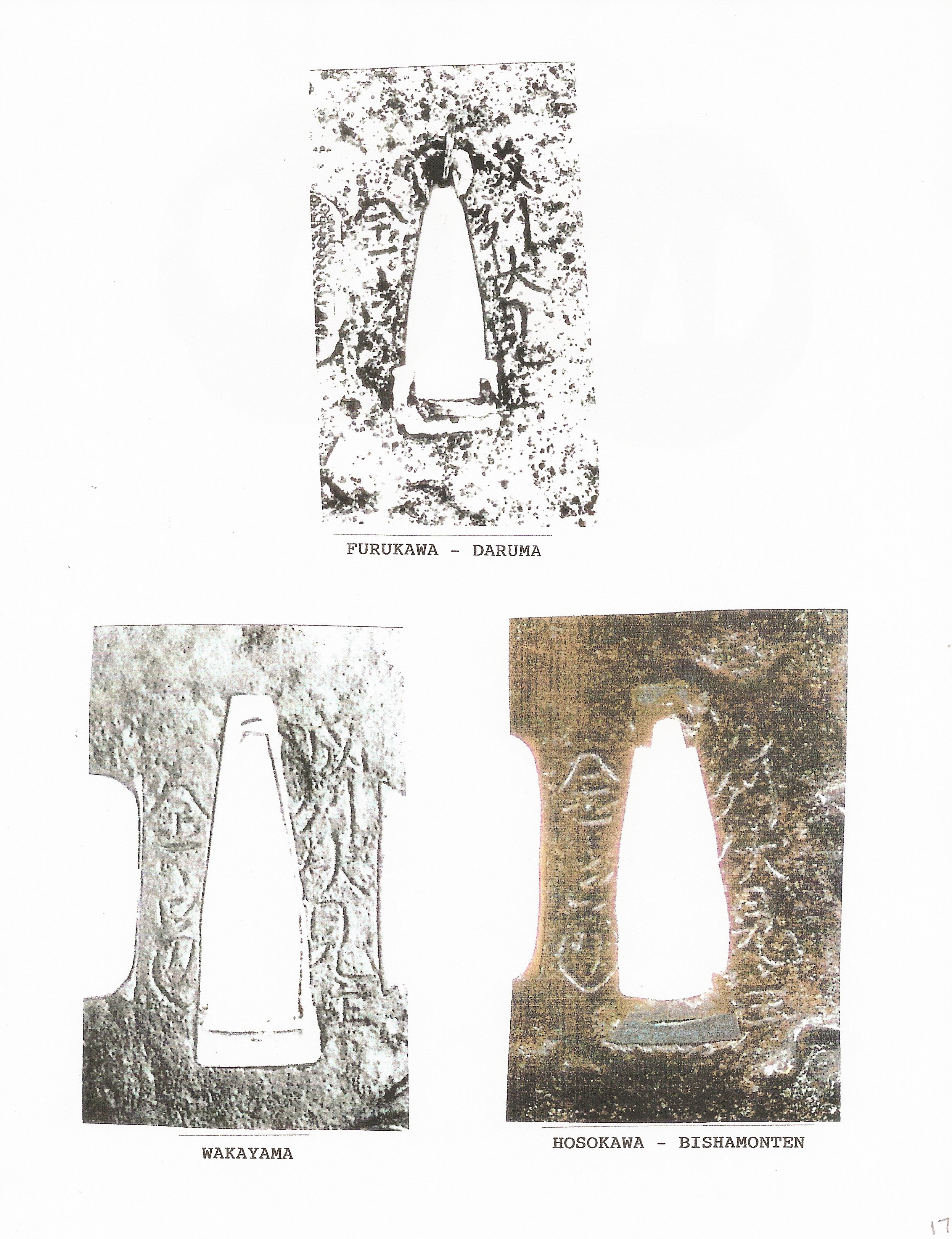

As you are aware there are only five tsuba with the signature: Joshu Fushimi ju Kansie. I am proud to say that I have held all five of these tsuba in my hand, and have examined them closely. These five tsuba have been published in one volume. Torigoye Kazutaro: TSUBA KANSHOKI, Okayama, Nihon bunkyo, 1964, 525 pages, 500 copies. On page 74, top, is the Baron Furukawa tsuba that he obtained from Wada. It is considered the earliest example with this signature. It is also illustrated in many other books, as well as in the Furukawa-Wada catalog. Unfortunately none of the photographs do it justice. On the bottom of this same page is the Mosle Kaneie, which I will go into more detail later, but Dr. Torigoye considered this the second oldest example. On page 75 is the face and reverse of the Marquis Hosokawa Kasuga Shrine tsuba. In 1960 I was shown this masterpiece at the National Museum in Ueno Park, by Dr. Sato. The iron, at that time, was so beautiful that I would have gladly traded my whole collection for this one tsuba. In 1992, I saw it again and it had been badly "cleaned" and much of the beauty of the original plate has been lost. Still I would give a fortune for it. On page 76 is the face and reverse of the Marquis Hosokawa tsuba, with the design of Bishamon Ten. This tsuba is very strong, particularly the shape and rim edge. On page 77 is the face and reverse of the ex Baron Ikeda tsuba that is now in the Wakayama collection. In 1960 this tsuba was offered for sale by Mr. Hayashibara, whose family had been the chief clerks to the Ikeda Daimyo for generations. Dr. Torigoye asked me if I would like to bid on it. He submitted my bid, with a top of $4,000, but I was out-bid by Mr. Wakayama. Years later I told Wakayama this story and he said: "So, you are the one who gave me so much trouble!" We both had a good laugh that day. It is strange that I paid only a little more for the Mosle Kaneie. Naturally the Wakayama Joshu Kaneie would be worth forty times what it cost in 1960, if it were ever for sale today.

With this short overview you will understand the rarity and importance of these five tsuba. One could write volumes about these tsuba and the rest of the Kaneie school, and someone should do just that.

As you see from this the Kaneie family school living at Fushimi in Yamashiro Kuni were a large group of artists who were very concerned about their image and felt very proud of where they lived. Years ago when I asked John Yumoto why they put such a full residence on their tsuba, he said "It was good advertising for their product." Why are there only five Joshu signature tsuba? I have one theory. This signature was carved by the earliest professional signing artist of this family school group. He died or moved away and the succeeding signing artists of the school were to use the Yamashiro Kuni signature to show more prestige and importance to their work. If anyone has other theories or ideas I would very much like to hear them.

Now I wish to explain why I am absolutely convinced that the Mosle tsuba is from the same hand, and signed by the same person as the other four Joshu Kaneie tsuba. Since there are only five examples with this signature they all share a common bond, both in workmanship and period of production. Which was before the Edo period, how early is still hotly debated. None of them was known to exist except by the keepers of the store houses (kura) of the noble families who owned them. The two examples in the Marquis Hosokawa collection are said to have come into his possession from the following story. The Hosokawa Daimyo was having an audience with his retainers when he noticed the Kasuga shrine tsuba on the sword of one of his lieutenants. He admired it and told the vassal so. The retainer went back to his quarters and removed the tsuba from his sword and put it in a box to present it to his master. Only the slightest admiration of an object owned by an underling would require this response. The Bishamon Ten tsuba seems to have entered the Hosokawa family collection in the same manner. None of these five tsuba were known beyond the Daimyo class until the late Edo period and some not until the Meiji era. They were kept in secret by their owners and occasionally mounted on their swords but they still could not be seen by the public, or any artists at that time. Why none of these five tsuba could be a forgery is as follows. To make a forgery one has to have an object to copy or imitate, since none of these tsuba could be seen by an artist who might copy them, no artist would be able to make a forgery. You can not copy something that you have no idea what it looks like. On the other hand the Kaneie tsuba that are signed with the Yamashiro Kuni signature were known more commonly and could be seen on the swords of lower class samurai. At the beginning of the Edo period when the artists at Fushimi moved to Saga in Hizen Province to work for the Nabeshima Daimyo they produced hundreds to copies of the Yamashiro signature during most of the next three hundred years. The same style of copies were also made in Kyoto and at Aizu in Iwashiro Province . One will see by the quality of the copies that they had not seen a genuine example made in the Momoyama period, or before. They must have made their copies from rubbings taken with them in their move to Saga. All the plates are of the typical Edo period thickness and they did not realize that much of the high relief iron design was actually iron on iron inlay. Many of the designs seem to have been taken from paintings of the Edo period rather than those of the Muromachi period. Also there are NO Edo period copies signed with the Joshu signature, all are signed with the typical Yamashiro Kuni signature. In fact there are no copies of these five tsuba to be found anywhere. As for the design subjects found on the five Joshu tsuba one may see later examples of the Yamashiro Kuni signature where the same subject did occure, but none of them seem to have been directly taken from the Joshu originals. The Baron Furukawa Daruma tsuba has at least six examples signed with the Yamashiro signature, but none of them are close in style or quality to the Joshu original. The Marquis Hososkawa Kasuga shrine subject is unique as there are no later tsuba with this subject that have been recorded so far. The Bishamon Ten design subject is found in one other example with the Yamashiro signature but it was not copied from the Joshu original, and the quality is far inferior. As for the Joshu Mosle example there are at least three examples signed with the Yamashiro signature that have a version of this subject but none of them have a passenger in the boat or the details in the carving and the iron on iron inlay to be found in the original Joshu tsuba. The Mosle example was not used for a model for any of them, also the design of hare on waves with silver moon can not be found on any of the Yamashiro signature examples. The Wakayama Joshu tsuba subject of skull and bones can be seen in at least two examples signed with the Yamashiro signature but neither was taken from the Joshu example. Thus it would seem that none of the artists who made the Yamashiro Kuni examples actually saw any one of the Joshu tsuba. The same may be said for all the Edo period Kaneie examples. From these comparisons we may deduce that the artists who made the tsuba with the Yamashiro Kuni signature never saw any of the Joshu signature examples. It has always been my theory that there were a group of artists who made the tsuba signed with the Yamashiro signature and one or more professional signers who carved the signatures on these pieces. This group effort was needed to supply the vast number, at least 150,000 or more, of fully mounted swords that were shipped to China and Korea in the Muromachi period. But then as you may know the export of swords to China and Korea requires years of study and research that will also tell us a great deal about the Kaneie tsuba made in Fushimi, and I think mounted on these export swords. If some student collector would like to take on this project we could all learn a great deal from such a project.

By this time I am sure you must have realized that this is the single rarest and most important tsuba outside of Japan. This "hakogaki" must be the longest and most uberous ever written, and the only one I shall ever write.

I would like to thank the following for their input, editorial help, and their years of friendship. Stuart E. Broms, Monte Jay Cox, Alan Harvie, Elliott Long, Sebastian Izzard and William Jay Rathbun.

What do I see when I hold the Joshu Kaneie in my hand and in bright sunlight? First the plate. The center is 1mm (0.04 inches) thick. The rim is 2mm thick. The iron on iron inlay varies from 2mm to 4mm above the plate surface. The thickness from the rabbit on the reverse to the boatman on the face is 5mm. The plate color is a very deep purple, to a rich, almost satin black. This is the same colors that I saw in the Hosokawa Kasuga Joshu tsuba. The original rim is now cut away and the original shape of the plate is not sure. The nakago-ana has been moved to the right and made smaller than the original. The large sukashi opening on the left, now in stupa or gravestone shape has been enlarged so that the left half of the KANEIE signature has been cut away. When were these alterations done? From the plate metal and the gold rim cover, which matches the gold on the plate, in both color and quality, it would seem the work was done very shortly after the original plate was made. Within a generation. Why was it done? Someone wanted to mount this tsuba on a tanto blade and had the original artists alter it for that use. You must remember that the tsuba of this period were utilitarian and have become great art objects only hundreds of years after they were made. When it was new it was not judged on aesthetic grounds, but how it could best serve the owner.

The iron on iron inlay is so skillful that you cannot see the edges of the inlay. The boatman has a silver face, hands, and legs, with gold flush inlay rings on his robes. The passenger has silver face and gold mon on his robes. The spire of the pagoda is in silver. The reverse has a full silver moon, and the ears of the rabbit are in silver with carved details, his eye is gold. The plate surface is worked and hammered in a gentle way that is typical of this artist.

Mosle - Haynes

| Return to R. Haynes Literary 'Works' OR Home Page - Email to Shibui Swords |