"TAMESHI-GIRI” and “SUEMONO-GIRI”:

THEIR MEANINGS, HISTORY AND

PRACTICE.

S. Alexander Takeuchi, Ph.D.

Department of Sociology

University of North Alabama

June 30, 2003

I. Introduction.

The term “tameshi-giri” as a martial art jargon imported from Japan has already been used widely in the Western world. However, except for some highly advanced and traditional JSA practitioners outside of Japan who may understand the historic meanings and purposes of “tameshi-giri” as it was used by samurai in the old days of Japan, most JSA practitioners in America (both advanced and less advanced) seem to be using this term more loosely.

In the context of the JSA community in the Western world today, the term “tameshi-giri” seems to be used more generally to refer to “the practice of cutting traditional targets (e.g., maki-wara, goza, tatami-omote, bamboo, etc.) for the purpose of testing/developing the skill of the practitioner in the use of Japanese swords.” Not surprisingly, because of the changes in the practice of “tameshi-giri” in Japan over its course of history, this modern definition of “tameshi-giri” also seems to be shared widely by today’s sword art practitioners in Japan.

“Suemono-giri,” on the other hand, is a term that not many JSA practitioners in the Western world are familiar with. It is a rather old-fashion JSA jargon that modern practitioners in Japan do not use very often, unless the context specifically calls for this more narrowly defined term. Nonetheless, when average Japanese hear this somewhat unusual word, “suemono-giri,” they tend to imagine a samurai or a skilled JSA practitioner performing various cuts on stationary targets made of maki-wara, goza, tatami-omote, etc. to see/develop his ability to perform proper cutting techniques.

In both instances, the connotations that “tameshi-giri” and “suemono-giri” convey today seem very similar (if not the same): They are basically viewed as “the means to test and/or develop the skills of swordsmen in the use of Japanese swords.” In such a context, the only differences in connotation between these two terms appear that:

1) the term “tameshi-giri” tends to emphasize the purpose of cutting - “to test” (= “tameshi”), while the term “suemono-giri” tends to emphasize the object/target to be cut - “fixed/still object” (= “suemono”);

2) the term “tameshi-giri” is more commonly used than the term “suemono-giri.”

The question still remains, however, if they really mean the same activity and/or if they were also used as synonyms in the old days. Actually, examinations of semantics of these two terms and the historical contexts in which “tameshi-giri” and “suemono-giri” had been performed more commonly reveal interesting facts that might not have been known to many in the JSA community of the Western world.

II. The Semantics of “Tameshi-giri” and “Suemono-giri.”

Although the terms “tameshi-giri” and “suemono-giri” are often used as synonyms (with slightly different emphases) today, the semantics of the kanji used in those terms are quite different. The word “tameshi” in “tameshi-giri” is the noun form of a verb “tamesu,” which simply means “to test.” Thus “tameshi-giri” literally means “test-cutting.” On the other hand, “sue-mono” in “suemono-giri” is a composite noun that consists of a) the adjective form of a verb “sueru,” which means “to fix on something” or “to place still on something,” and b) a noun for “(non-living) object.” Hence, “suemono-giri” literally means “fixed (non-living) object cutting.”

As it is obvious from the semantics of the kanji, the word “tameshi-giri” does not indicate (either explicitly or implicitly) by itself “what is to be tested” by cutting. In other words, the semantics of the term itself does not specify whether it is “to test the quality of the blades” or “to test the skills of the swordsman.”

Similarly, the semantics of the kanji for “suemono” does not indicate “what this ‘fixed/stationary object’ really is.” In other words, it does not specify whether the “fixed object” is “corpse” or other more commonly available targets such as maki-wara, goza, tatami-omote, etc. However, one thing that the knji for “-mono” (=object) indicates is that it is *not* a “live human” as there is another kanji that also reads “-mono” yet means “human” (not used in the word “suemono-giri”).

Of course, the examination of mere semantics of those terms cannot clarify anything specific regarding the cultural practice of “tameshi-giri” and “suemono-giri” or their history. Nonetheless, one thing it clarifies is that the former is a more general term (thus, a broader category of behavior), whereas the latter is a specific “sub-category” of the former. In other words, the semantics of those terms indicate that “tameshi-giri” is a broader category of behavior of “general test-cutting,” whereas “suemono-giri” is its specific sub-category in which “the test-cutting is performed through the use of ‘fixed/still (non-living) objects’ as the cutting medium.”

This in turn indicates that, at least logically, there are other forms (=sub-categories) of “test-cutting” within the broader category of “tameshi-giri” than the use of “fixed/still (non-living) objects” as the cutting medium. This leads us to the next level of analysis based on the cultural meanings of those terms as defined academically.

III. The Cultural Meanings and Connotations.

To understand what “tameshi-giri” and “suemono-giri” actually refer to in the Japanese language, thus to understand the cultural meanings and connotations of these terms, it is necessary to first examine the definitions of these terms presented in Japanese language dictionaries. According to the online version of Daijirin (Sanseido, 2003), a modern Japanese-Japanese encyclopedic dictionary, the term “tameshi-giri” is defined as “the procedure to test the cutting ability of swords by cutting humans and animals.” In another Japanese-Japanese dictionary (Hisamatsu and Sato, 1976), “tameshi-giri” is defined as “to cut humans or maki-wara in order to test the cutting ability of swords.” [Note: The original Japanese definitions found in the dictionaries are translated into English by this author. There is no definition for the term “suemono-giri” in either dictionary.]

Despite the fact that none of the kanji used in “tameshi-giri” semantically indicates the objectives/purposes of “tameshi-giri,” Japanese dictionaries clearly define “tameshi-giri” with its intended objective and purpose: That is, “to test the cutting ability/quality of the blades,” rather than the swordsman’s skills. Furthermore, the definitions provided by two respected Japanese language dictionaries even specify the most common or prototypical “cutting medium” for traditional “tameshi-giri” - “humans” (though they do not specify corpse or live humans).

Of course, to cut “humans” (or even animals), whether dead or alive, to test the cutting ability of swords is legally and morally condemned in modern Japanese society. It is also a common knowledge both in and outside of the JSA community that “tameshi-giri” today almost exclusively means “test cutting of stationary targets made of maki-wara (or similar materials) as the test medium” to check the skill of the swordsman more than to check the quality of the blades.

Then, why do Japanese dictionaries still define “tameshi-giri” essentially as “the test of swords by cutting humans”? The most logical answer is that “tameshi-giri” as practiced in the days of samurai in fact meant “the test of swords by cutting humans.” This leads us to the next level of examination of these terms from historical and ethnological perspectives.

IV. “Tameshi-Giri” and “Suemono-Giri” from Historical and Ethnological Perspectives.

A. The usage of “tameshi-giri” and “suemono-giri” in historical documents.

The records of “tameshi-giri” start appearing frequently in historical documents (both in the public records compiled by the national and local governments as well as in the writings by private authors) from the mid 1600's, though the word “suemono-giri” does not appear as often. In existing historical documents, the terms “o-tameshi” or simply “tameshi,” instead of “tameshi-giri,” are most commonly used to refer to “test of swords.” In those documents, “otameshi” or “tameshi” all mean the same thing - “to test the cutting ability of the swords by cutting convicted felons who had committed serious crimes (by the cultural/legal standard of the society during the time) mostly after they were decapitated but sometimes as the means of execution (Ujiie, 1999).

The words “suemono-giri” and “suemono” appear much less frequently than does “tameshi” or “otameshi” in the history of Japan. However, when “suemono” appears in historical documents, it mostly refers to “a specific form of ‘tameshi’ in which a decapitated corpse of convicted felon was securely placed on an elevated soft soil to be used as ‘fixed’ test medium for “tameshi” (Kodera, 1724; also see Hachiya, 1814). Additionally, the word “suemono” was also used to form compound nouns as “suemono-shi” (= an expert/professional in “fixed target” tameshi-giri) or “suemono no waza” (= the techniques of “fixed target” tameshi-giri) (Ujiie, 1999).

B. Criminal justice practice vs. martial arts practice.

As the historical documents clearly indicate, the term “tameshi-giri” was rather closely related to the criminal justice practice during the Edo period (Ujiie, 1999). On the other hand, the term “suemono-giri” was used both as the “specific form of ‘tameshi-giri’ as well as the skills and abilities of the swordsmen to perform ‘tameshi-giri’ using decapitated corpse as stationary target/test medium. In other words, historically “tameshi” was mostly performed as test cutting of convicted felons to evaluate the quality of swords within the legitimate context of criminal justice system in the old days of Japan, whereas “suemono-giri” was not only practiced as such but also practiced as a comprehensive techniques of performing specific form of “tameshi” (namely “dotan-giri” to cut decapitated corpse) that were developed and learned within the martial arts context.

To substantiate the notion of “tameshi” as a part of legitimate criminal justice practice, a number of historical documents written between the mid 1600s to early 1800's describe the specific details and procedure of “tameshi” as part of the public execution ritual (Ujiie, 1999). In those public records, “tameshi” using the corpse of executed felon as a form of extra punishment (because even felons wanted their bodies to be handed to their families for proper burial) seems to be the norm rather than exceptions at least till the late 1700's to early 1800's.

C. The frequency of “tameshi” as the cultural practice of the samurai.

The practice of “tameshi” to test their personal weapons was so popular amongst higher ranking samurai that many historical documents (including famous Hagakure) describe how samurai in the 1600's tried to receive or buy corpses of executed felons from the local correctional facilities (Ujiie, 1999). Also to meet the demands for more corpses for “tameshi,” most felony offenders convicted in the courts in the capital city of Edo were also used as “suemono” (i.e., the medium for “tameshi”) until the late 1600's. Additionally, since higher ranking “hatamoto” and daimyo lords were also given complete criminal justice authority over their samurai class subordinates and civilian class servants, those who judged to be felons by their masters were also executed and used as the medium for “tameshi” until the mid 1600's (Shinmi, 1732)

Then the demand for corpses became so high to the extent that wealthy samurai in the mid 1600's started using corpses of people who were drowned or starved to death. Because of the unregulated use of corpses for “tameshi” by eager samurai, several han (i.e., state/provincial) governments eventually issued prohibitions against the use of corpses for “tameshi” other than those of the executed felons legally received through the local correctional facilities (Ujiie, 1999). Such legal restrictions also contributed to the decline of “tameshi” to be a rather restricted ritual within the context of criminal justice procedure than common martial arts practice of the samurai class that it once had been.

D. Who were used as “suemono” (i.e., stationary medium for

“tameshi”)?

Along with the decline of the practice of “tameshi” amongst the samurai class since the mid 1700's, the shogunate and local governments started amending their penal laws to include exemptions for “tameshi” based on the social classes and gender of the felons in addition to the severity of the crimes they had committed. By the late 1700's to early 1800's, the Tokugawa Shogunate and several “han” governments had issued prohibitions against the use of executed felons in the following categories (Ujiie, 1999):

1. Samurai or clergy (in the jurisdictions of the Shogunate);

2. Female felons (in the jurisdictions of the Shogunate, Owari and Takasaki Provinces);

3. Felons convicted of manslaughter instead of premeditated murder (in the jurisdiction of Hiroshima Province).

E. Who

actually performed “tameshi” on corpses?

This is one of the areas in which misconceptions are still perpetuated amongst many JSA practitioners particularly those outside of Japan. To understand this issue more accurately, it is necessary to place the notion of “tameshi” (and the use of corpses) in historical perspective.

As many already know, the time during which the samurai class had ruled Japan was about 675 years. During the 1600's, the samurai class had still maintained strong warrior class mentality, and thus had also tried to maintain the weaponry and martial skills necessary for their primary role as the warrior class. While I do not have any reference sources on “tameshi” prior to the Edo period (1603-1867), it is clear that by early 1600's the practice of “tameshi” on corpses had already been established as a legitimate means to test the quality of swords amongst the samurai class as well as a legitimate form of penal ritual in the criminal justice system of old Japan.

During this early stage of the Edo period, many high ranking samurai, including Daimyo lords actually engaged in the practice of “tameshi” on corpses by themselves as it was considered very legitimate and necessary practice embedded in their warrior class sub-culture. In fact, many existing historical records propr to the early 1700's clearly describe the practice of “o-tameshi” (i.e., a more formal and respectful form of the term “tameshi” used only when it was done for or by the Shogun or Daimyo lords) performed by those highest ranking samurai lords to admire the honorable spirit and tradition of the warrior class. For instance, those daimyo lords who were well documented in historical records to have performed “o-tameshi” on corpses by themselves include (Ujiie, 1999):

a) Tokugawa Yorinobu (a son of Tokugawa Ieyasu and the 1st Lord of Kii province);

b) Tokugawa Yorifusa (another son of Tokugawa Ieyasu and the 1st Lord of Mito province);

c) Tokugawa Mitsukuni (a son of Tokugawa Yorifusa and the 2nd Lord of Mito province);

d) Nabeshima Naoshige and Katsushige (the Lords of Saga province, father and son);

e) Honta Masakatsu (the Lord of Kohriyama province);

f) Hosokawa Tadatoki and Tadatoshi (the Lords of Kokura province, father and son);

g) Horie Tadaharu (the Lord of Matsue province).

As it is obvious from existing historical records, at least until the mid 1700's, to test the cutting ability of their weapons on corpses of executed felons had not been considered as uncivilized or inhumane acts to be deprecated (Ujiie, 1999).

Despite the efforts of higher ranking samurai to try to maintain their honorable spirits and martial skills, the long peaceful environment of the country and the wave of civilization clearly started affecting the mentality and daily customs of the samurai class since the 1700's. That is, the samurai were no longer the actual warrior class: Rather they had mostly become the advantaged class of government bureaucrats. Because of the declined needs for maintaining the martial skills as warriors, “o-tameshi” performed by higher ranking samurai themselves had no longer been popular by the mid 1700's (Ujiie, 1999).

During this time of decline of “o-tameshi” practice by the nation’s highest ranking samurai, professional sword testers (but not ordinary executioners) that were called “otameshi-geisha” or “suemono-shi” (relatively lower ranking samurai with recognized skills in swordsmanship who expertly performed “o-tameshi” on behalf of those higher ranking samurai) started appearing in history. By the mid 1700's, the Tokugawa Shogunate and its Osak and Nara Bugyo-sho (district magistrate offices), as well as Aizu, Owari, Saga, and Satsuma provincial governments, (some of whose rulers had been famous for practicing “o-tameshi” by themselves till the mid 1600's) all started hiring or commissioning to have the professional “otameshi-geisha” or “suemono-shi” (all of whom were samurai) to test the swords of high ranking samurai on their behalf (Ujiie, 1999).

F. Did “Eta” and “Hinin” classes actually perform

“tameshi” on corpses?

This is another area in which misconception is commonly perpetuated. Though by the late 1700's many higher ranking samurai had now stopped actually performing “o-tameshi” by themselves, “tameshi” practice itself was still the privilege and important cultural ritual limited only to the samurai class (Ujiie, 1999).

As far as the historical records indicate, even after the practice of “tameshi” had been considered uncivilized and inhumane, “tameshi” on corpses was still conducted and actually performed by the hands of none other than the samurai class professionals or executioners, but never by the hands of the lowest class “Eta” or “Hinin” (see Ujiie, 1999). Contrary to the widely spread misconception, eta and hinin were only employed as actual executioners to perform death penalty other than decapitation. Additionally, those in the lowest casts were merely used as assistance for “tameshi” to carry, move and set up the corpses on the stand for the samurai class “suemono-shi” to actually perform “tameshi” to test the quality of the swords owned by high ranking samurai (see, Fujita, 18xx; Hachiya, 1814 for detail).

Aside from the existing historical records, there were at least two obvious reasons that the samurai (who wanted their blades to be tested) would never have allowed the lowest casts of “eta” and “hinin” to actually test or even handle their precious blades. One is the existence of rather strict and detailed legal requirements imposed by the Shogunate and local governments for the proper procedure of “tameshi” rituals. Because “tameshi” was also performed as a part of legitimate criminal justice procedure (i.e., harsher punishment in addition to mere execution), these laws clearly designated the actual performer of test cutting only to the qualified samurai along with specific procedures of the ritual (Hachiya, 1814; Ujiie, 1999). Once again, those who actually performed decapitation of felons and “tameshi” were either a) doshin class samurai (i.e., the lowest ranking criminal justice officers) who were skilled in swordsmanship or b) professional “suemono-shi” (who were also samurai) commissioned by the appropriate magistrate office or by the owners of the swords being tested.

The other reason that eta and hinin could not have been allowed to test swords after executions of felons was the symbolic meaning of swords to the samurai class. Those swords being tested were private property of higher ranking samurai who requested their swords to be tested through the magistrate’s office. As many in the JSA community already know, the samurai of the past believed and actually treated their personal swords as though they were their own souls. As a matter of fact, those swords to be tested were first handed out to the bugyo (i.e., the chief magistrate officer), then to the yoriki (i.e., deputy chief), and finally to either doshin (i.e., the lowest ranking officer) performing executions or “suemono-shi” (i.e., samurai class professional sword testers); but never to be in the hands of the lowest class assistants who were literally regarded by samurai “less than humans.”

Another widespread misconception is that many of those who actually performed “tameshi” did not possess much sword skills. Existing historical records also tend to refute such a notion. Despite the fact that most of those sword testers were relatively lower in bureaucratic hierarchy, they often owned their own dojo of “suemono-giri” (i.e., specialized techniques of cutting stationary targets for the purpose of “tameshi”) and had several students entirely dedicated to perfect the skills of “suemono-giri” (see Ujiie, 1999 for detailed information on this). Since the swords being tested were the properties of higher ranking samurai, the owners of precious swords would not have trusted their family heirlooms in the hands of unskilled testers.

G. To what extent professional “tameshi-geisha” and “suemono-shi” were deprecated in Japan?

Once again, to fully understand this issue, it is necessary to place the notion of “tameshi” in historical perspective, and analyze how the cultural practice of “tameshi” itself had changed its meanings over the course of Japanese history. During those 260 years of Edo period, “tameshi” practice had always been a privilege of the samurai class. Especially in the early Edo period when some of the nation’s highest ranking samurai were performing “o-tameshi” by themselves, several of those dedicated samurai lords had even become the students of well recognized early “suemono-shi” in their own states (Ujiie, 1999).

For example, one of the earliest documented “tameshi” professionals in the early Edo period, Nakagawa Saheita Shigeyoshi, was a high ranking hatamoto class samurai with 1,200 koku territory of his own (Ujiie, 1999). Also as in the case of Aizu province, up until the early 1700's many of those “tameshi” professionals were well respected by the ruling lords of their provinces.

Those honorable days for professional “otameshi-geisha” and “suemono-shi” did not last too long especially since the mid to late 1700's when many high ranking samurai started viewing the practice of “o-tameshi” unnecessary, uncivilized and inhumane. Nonetheless, the practice of “tameshi” as a part of legitimate criminal justice procedure still survived more as a ritual till the end of Edo period. Many historical documents compiled in the mid to late Edo period indicate that the ritualistic practice of “tameshi” on corpses was carried out with dignity before the presence of high ranking officials (see Ujiie, 1999).

From the economic point of view, however, the annual salaries of those “tameshi-geisha” in the Edo period were not very high. Except for Nakagawa Saheita (who was a high ranking hatamoto himself with his own governing territory), his student Yamano Kanjuro/Kaemon (i.e., the teacher of the 1st generation Yamada Asauemon), and the famous 1st generation Yamada the “Kubikiri” Asauemon (but not later generations Yamada Asauemon), all seemed to have received relatively modest salaries and not so high of official ranks, though they were still well respected in their professions. Combined with the general decline of the demand for “o-tameshi” and the emerging cultural norms to view “tameshi” on corpses as an uncivilized act, most of so called “tameshi-geisha” or “suemono-shi” other than the famous Yamada Asauemon linage had eventually disappeared from the front stage of history.

One interesting piece of history about the famous Yamada family is that they also supported their family economy and the dojo management by engaging in the making of “medicine” by extracting some chemical essence from the kidneys of the corpses they had used for “tameshi” (Ujiie, 1999). Because of their other family business and the monopolized “o-tameshi” commissions from the Shogunate, the Yamada family, despite they remained “ronin” (i.e., samurai who did not have a particular master lord nor possessed any permanent administrative positions at the government) in official record, had maintained wealth till the end of the Edo period. According to historical records (see Fukunaga, 1970; Ujiie, 1999), the Yamada family continued their monopoly in the “o-tameshi” commissions for the Shogunate till the Meiji Restoration. The 8th generation Yamada Asauemon Yoshitoyo and his younger brother Yoshifusa both became correctional officers in Tokyo under the new Imperial government. However, in the new domicile registration record implemented by the Imperial government in 1873 (to replace the old “Shi (samurai),” “No (farmers),” “Ko (craftsmen),” and “Sho (merchants)” casts of the Edo period), they were registered as “Hei-min” (commoners), not “Shi-zoku” (i.e., a new name/category created for the old samurai class).

In sum, most “tameshi” professionals did not have high ranks in the government bureaucracy, nor much wealth (except for the famous Yamada family): However, their skills in the profession had been well respected overall until the end of the Edo period.

(For those who are interested in the history of Yamada Asauemon and his family, refer to Fukunaga, 1970 and Ujiie, 1999.)

V. “Tameshi-Giri” and “Suemono-Giri” in Japanese Sword Arts Today.

A. New meanings and practice of “tameshi-giri” in sword arts today.

In the previous sections, I mostly focused on the analysis of “tameshi-giri” to provide historically accurate accounts of this unusual cultural practice of the samurai class. In this section, I will try to summarize the meanings of the terms “tameshi-giri” and “suemono-giri” as they are currently used in the sword art community in Japan.

As I described earlier, the term “tameshi-giri” or more accurately “tameshi” referred exclusively to “the act of testing the swords on humans (mostly corpses but sometimes live felons)” in the history of Japan. Similarly, the term “suemono-giri” historically referred to “the specific act of performing ‘tameshi’ on decapitated copses mounted as fixed/still targets.” In both usages, there was no implication that the cuts were meant to be the tests of the swordsmen’s skills; rather, they strictly meant to be the tests of the blades’ quality and cutting ability by the hands of rather skilled swordsmen specialized in “suemono-giri” (thus, specialized in stationary target test cutting).

While those descriptions were historically accurate, it was also true that those “otameshi-geisha” and “suemono-shi” (i.e., professional sword testers) did not always have the “real” test medium, thus corpses, available for their daily training. Therefore, those who were specialized in “tameshi-giri” (whose primary forms were “suemono-giri”) mostly practiced their “suemono-giri” skills via cutting some other commonly available alternative mediums such as maki-wara, goza, bamboo, etc. that approximated the weight and density of corpses. Indeed, such efforts of “tameshi-giri” professionals in their daily training were also shared by avid kenjutsu and iai-jutsu practitioners of the old days to form the foundation of the modern notions of “tameshi-giri” and “suemono-giri” in JSA community.

Today, those JSA schools that emphasize practical applications also emphasize the modern notion of “tameshi-giri” as the test of their swordsmanship and as the means to perfect their skills to perform the original manifest function of the swords. In their regular training, they also strive to perfect their arts by cutting maki-wara, goza, tatami-omote, bamboo, etc. In this sense, the meanings of “tameshi-giri” and “suemono-giri” are completely different than what they had once meant to the people in Japan during the time of the samurai.

Though each school of sword art may have slightly different emphasis and interpretation, in today’s martial arts definitions, “tameshi-giri” primarily refers to “test cutting of common medium (that are supposed to simulate human flesh and bones) to evaluate the skills of the swordsman and as the means to develop proper skills to cut with swords.” Similarly, “suemono-giri” (though not as commonly used as “tameshi-giri”) as used in today’s martial arts context mostly refers to “the practice of cutting stationary targets to test and evaluate the skills of the swordsman.” The only exception to these modern notions, where the term “tameshi-giri” or “suemono-giri” still refers to the “test of the quality of the swords,” is the situation in which tosho (i.e., sword smiths) or commissioned sword art practitioners perform “test cuts of conventional targets using shinsaku-to (i.e., newly forged swords)” (Shibata, 1995; Tsuchiko, 1999).

B. Other related terms in modern sword arts.

Despite the widespread usage of the term “tameshi-giri” in the JSA community, the word “tameshi-giri” as it is defined in modern Japanese dictionaries still carries the old notions of “the test of swords” and “the use of humans,” which clearly contradict to the modern meanings of “tameshi-giri” that are now integral part of Japanese sword arts. To avoid confusion (because of the historical change in its meanings) and to clarify the purposes of “test cutting” (whether to test the swordsmen’s skills or the quality of the blades), a few other terms have already been introduced and being used by the practitioners of JSA today.

According to Toshishiro Obata (1996), the founder of modern sword art school “Shinkendo,” “tameshi-giri” can be divided into two categories based on its purposes: “shi-zan” and “shi-to.” According to Obata, the term “shi-zan” refers to the “test of the swordsman’s skills through the use of cutting mediums such as maki-wara, tatami-omote, and bamboo.” On the other hand, the term “shi-to” refers to the “test of the quality of the blades through the use of harder cutting mediums.” While Obata does not specify the “harder cutting mediums” for “shi-to,” they should at least include thicker bamboo (that was mentioned in another section of his writing) and possibly steel helmet…

References

Hisamatsu, S. & Sato, K. (Eds.) (1976). Kadokawa kokugo jiten. [Kadokawa Japanese-Japanese Dictionary.] Tokyo, Japan: Kadokawa-shuppan.

Fujita, Shintaro. (18xx). “Otameshi no zu.” [An illustration of test cutting.] In Tokugawa-bakufu keiji zufu. Tokyo, Japan: Meiji University Criminal Justice Museum.

Fukunaga, Suiken. (1970). Kubikiri Asauemon token oshigata. vol. 1 and 2. Tokyo, Japan: Yuzankaku.

Hachiya, Shingoro. (1814). Tokuringen Hirok. [The secret record of compassion and austerity of the Tokugawa Shogunate.] Tokyo, Japan: Japan National Public Record Library, the division of Cabinet Records.

Kodera, Nobumasa. (1724). Shijintsu. Yamagata, Japan: Tsuruoka City Public Library.

Obata, Toshishiro. (1996). “Tameshi-giri.” In Shinkendo Kaiso. International Shinkendo Federation. http://www.shinkendo.org/kaiso.htm

Shibata, Mitsuo. (1995). Shumi no Nihon-to. [Nihon-to for hobby.] Tokyo, Japan: Kogei Shuppan.

Sanseido. (2003) Daijirin [an encyclopedic Japanese-Japanese dictionary.] (An online version.) http://jiten.www.infoseek.co.jp/Kokugo?qt=%A4%BF%A4%E1%A4%B7%A4%AE%A4%EA&sm=1&pg=result_k.html&col=KO

Shinmi, Masatomo. (1732). Hachiju ou mukashi-banashi. [The old tales by eighty years old man.] Reprinted (1976) in Nippon zuihitsu taisei. [Great Japanese essays.] vol. I, No. 17. Tokyo, Japan: Yoshikawa Kobunkan.

Tsuchiko, Tamio. (1999). Nihon-to 21 Seiki he no chosen. [Nihon-to: The challenge toward the 21st century.] Tokyo, Japan: Yuzankaku.

Ujiie, Mikito. (1999). Oo Edo shitai ko: Hitokiri Asauemon no jidai. [Examinations of corpse in the great capital of Edo: The era of Hitokiri Asauemon.] Tokyo, Japan: Heibon-sha.

Appendex

List of popular sword testers in saidan-mei by C. U. Guido Shiller **

(Copyright © by C. U. Guido Shiller)

|

* Aoki Hikozaemon Eguyoshi [Alternative reading may exist.] |

青木彦左衛門抉之 |

(寛永 Kanei) |

|

Asahina Fujizaemon Tadanori |

朝比奈藤左衛門忠則 |

(寛文 Kambun) |

|

Ashizawa Genzaemon |

蘆沢源左衛門 |

(享保 Kyôhô) |

|

Dei Nizaemon |

出井仁左衛門 |

(寛永 Kanei) |

|

Gotô Gozaemon |

後藤五左衛門 |

(享和 Kyôwa) |

|

Gotô Tameemon |

後藤為右衛門 |

(文政 Bunsei) |

|

Hattori Kanemon |

服部勘右衛門 |

(元禄 Genroku) |

|

Hirano Sadahiko |

比良野貞彦 |

(享保 Kyôhô) |

|

Hitomi Dembê Shigetsugu |

人見伝兵衛重次 |

(寛文 Kambun) |

|

Iba Sakyô |

伊庭左京 |

(寛永 Kanei) |

|

Iga Shirôzaemon |

伊賀四郎左衛門 |

(天保 Tempô) |

|

Imai Umon Nobutada |

今井右門信猶 |

(文政 Bunsei) |

|

Inoue Bunshichirô Masazumi |

井上文七郎勝澄 |

(元禄 Genroku) |

|

Itani Chûzô Yoshikazu |

猪谷忠蔵之和 |

(元禄 Genroku) |

|

Itani Tadashirô Kazuyoshi |

猪谷唯四郎和賢 |

(享保 Kyôhô) |

|

Kakei Hannojô Tamekatsu |

筧半之丞為勝 |

(天保 Tempô) |

|

Kaneko Sukenojô |

金子助之丞 |

(寛永 Kanei ~ 寛文 Kambun) |

|

Kaneko Sukezumi |

金子助亟 |

(寛永 Kanei) |

|

Katada Kandayû |

片田勘太夫 |

(享保 Kyôhô) |

|

Komatsubara Jimbê Yoshimasa |

小松原甚兵衛良正 |

(文政 Bunsei) |

|

Kumada Tobê Tomosuke |

熊田戸兵衛友輔 |

(寛文 Kambun) |

|

Kuramochi Takeemon |

倉持竹右衛門 |

(享保 Kyôhô) |

|

Kuramochi Yasuzaemon |

倉持安左衛門 |

(享保 Kyôhô) |

|

Kuwayama Tango no Kami Sadamasa |

桑山丹後守貞政 |

(元禄 Genroku) |

|

Maejima Banemon Tomotsugu |

前嶋番右衛門友次 |

(寛文 Kambun) |

|

Maejima Hachirô Tomohisa |

前嶋八郎友久 |

(貞享 Jôkyô) |

|

Majima Sadazaemon |

真嶋貞左衛門 |

(享保 Kyôhô) |

|

Matsumoto Chôdayû Masatomo |

松本長大夫雅友 |

(元禄 Genroku ~ 享保 Kyôhô) |

|

Matsunami Shirobê |

松波四郎兵衛 |

(延寳 Empô) |

|

Matsunami Tokiemon |

松波時右衛門 |

(延寳 Empô) |

|

Mimura Masanobu |

三村正延 |

(元禄 Genroku) |

|

Miyai Rokubê no Jô Shigeyori |

宮井六兵衛尉重頼 |

(寛永 Kanei ~ 寛文 Kambun) |

|

Murai Fujiemon |

村井藤右衛門 |

(慶安 Keian) |

|

* Nagabatake (Nagahata) Shirobê [Valid alternative reading.] |

長畑四郎兵衛 |

(文政 Bunsei) |

|

Nakagawa Saheita Hidetsune |

中川左平太秀恒

|

(慶長 Keichô ~ 元和 Genna) |

|

* Nakanishi Tomozô (Jûzô) Yukimitsu [Valid alternative reading.] |

中西十蔵如光 |

(延寳 Empô ~ 元禄 Genroku) |

|

Narita Iemon no Jô |

成田伊右衛門尉 |

(元禄 Genroku) |

|

Nezu Saburobê no Jô Mitsumasa |

根津三郎兵衛尉光政 |

(元禄 Genroku) |

|

Ogasawara Tsubakinosuke |

小笠原椿之助 |

(享和 Kyôwa) |

|

Ogawa Hachirôemon Shigeharu |

小川八郎右衛門重治 |

(寛永 Kanei ~ 寛文 Kambun) |

|

Okamoto Katsuemon |

岡本勝右衛門 |

(貞享 Jôkyô) |

|

Ôkawa Hachiemon Nagatsugu |

大河八右衛門長次 |

(元和 Genna ~ 寛永 Kanei) |

|

Ônuma Jinzaemon Masashige |

大沼甚左衛門正重 |

(寛文 Kambun) |

|

Ôzawa Utanosuke |

大沢雅楽助 |

(享保 Kyôhô) |

|

Sano Tomonoemon |

佐野伴之右衛門 |

(享保 Kyôhô) |

|

Shibazaki Denzaemon Masatsugu |

柴崎伝左衛門正次 |

(寛文 Kambun) |

|

* Sudô Godayû Rikusai [Alternative reading may exist.] |

須藤五太夫睦済 |

(天明 Temmei) |

|

Sugisaki Matazaemon Shigesada |

杉崎又左衛門重貞 |

(天和 Tenna) |

|

Sugisaki Shinemon no Jô Morishige |

杉崎新衛門尉森重 |

(天和 Tenna) |

|

Sumi Motooki |

角元興 |

(嘉永 Kaei ~ 慶応Keiô) |

|

Tani Dewa no Kami Hiratomo |

谷出羽守衡友 |

(天正 Tenshô ~ 文禄 Bunroku) |

|

Tomita Yaichizaemon no Jô Shigetsuna |

富田弥一左衛門尉重綱 |

(延寳 Empô ~ 天和 Tenna) |

|

Ukai Jûrôemon no Jô Yoshizane |

鵜飼十郎右衛門尉義真 |

(元禄 Genroku) |

|

Umezawa Rokuzaemon |

梅沢六左衛門 |

(寛文 Kambun) |

|

Utsuki Hachizaemon no Jô Nagatoki |

宇津木八左衛門尉長時 |

(寛永 Kanei) |

|

Watanabe Sannoemon no Jô Shigetsuna |

渡辺三之右衛門尉重綱 |

(寛文 Kambun) |

|

Yamada Asaemon Sadatake |

山田浅右衛門貞武 |

(寳永 Hôei) |

|

Yamada Asaemon Yoshihiro |

山田浅右衛門吉寛 |

(明和 Meiwa ~ 天明 Temmei) |

|

Yamada Asaemon Yoshimasa |

山田浅右衛門吉昌 |

(天保 Tempô) |

|

Yamada Asaemon Yoshimutsu |

山田浅右衛門吉睦 |

(天明 Temmei ~ 文化 Bunka) |

|

Yamada Asaemon Yoshitoki |

山田浅右衛門吉時 |

(享保 Kyôhô) |

|

Yamada Asaemon Yoshitoshi |

山田浅右衛門吉利 |

(嘉永 Kaei) |

|

Yamada Asaemon Yoshitoyo |

山田浅右衛門吉豊 |

(安政 Ansei) |

|

Yamada Asaemon Yoshitsugu |

山田浅右衛門吉継 |

(元文 Gembun) |

|

Yamada Gengorô |

山田源五郎 |

(天明 Temmei) |

|

Yamada Genzô |

山田玄蔵 |

(元文 Gembun) |

|

Yamada Genzô Yoshigimi |

山田源蔵珍公 |

(天明 Temmei) |

|

Yamada Gonnosuke Yoshitaka |

山田権之助吉隆 |

(文化 Bunka) |

|

Yamada Gosaburô |

山田五三郎 |

(弘化 Kôkai) |

|

Yamada Yoshitoyo |

山田吉豊 |

(安政 - Ansei) |

|

Yamanaka Kanzaburô Tomoshige |

山中勘三郎智重 |

(萬治 Manji) |

|

Yamano Kaemon no Jô Nagahisa |

山野加右衛門尉永久 |

(寛永 Kanei ~ 寛文 Kambun) |

|

Yamano Kanjûrô Hisahide |

山野勘十郎久英 |

(萬治 Manji ~ 元禄 Genroku) |

|

Yamano Kichizaemon Hisatoyo |

山野吉左衛門久豊 |

(貞享 Jôkyô ~ 元禄 Genroku) |

|

Yashima Shôbê |

矢島庄兵衛 |

(寛文 Kambun) |

|

Yomogida Andayû |

蓬田安太夫 |

(寛文 Kambun) |

|

*Yoshida Bumpei (Fumihira) [Valid alternative reading.] |

吉田文平 |

(文化 Bunka) |

|

Yoshida Gempachirô |

吉田源八郎 |

(文政 Bunsei) |

|

Yoshida Sadazaemon |

吉田定左衛門 |

(享保 Kyôhô) |

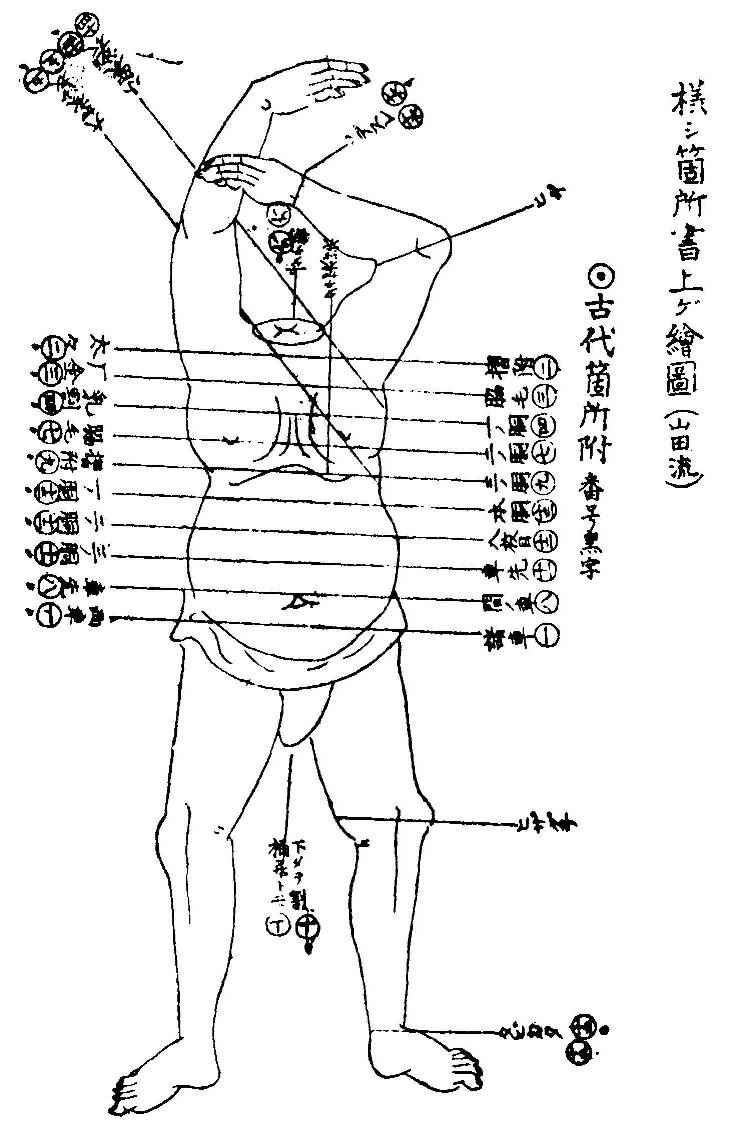

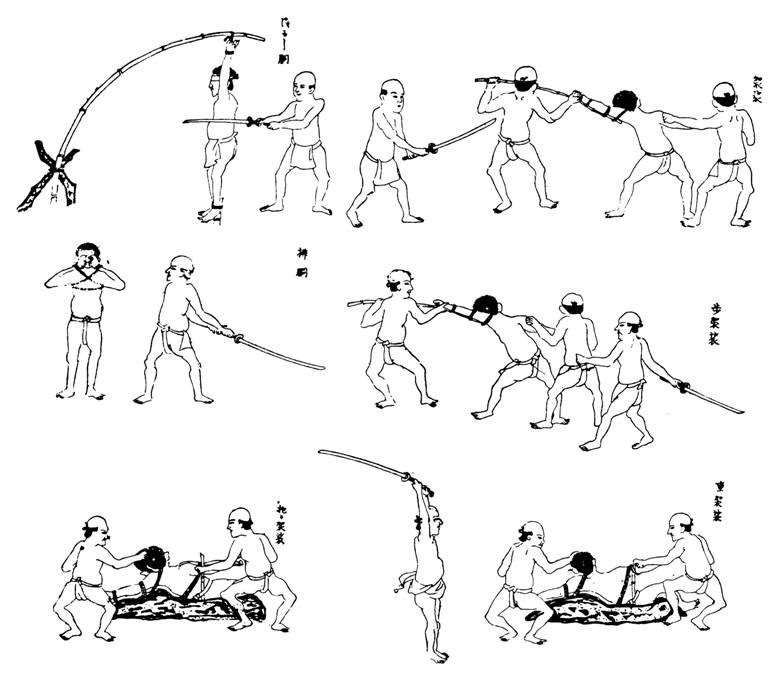

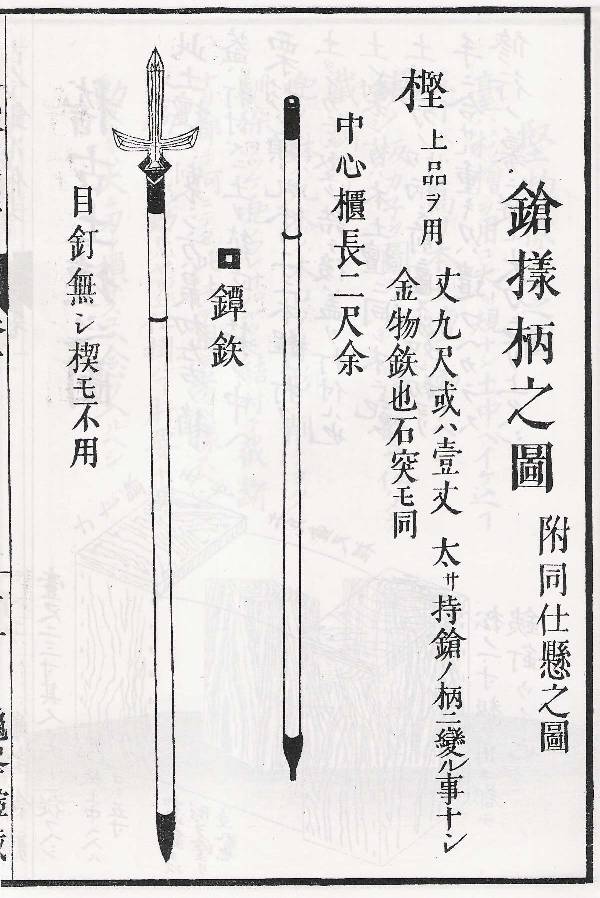

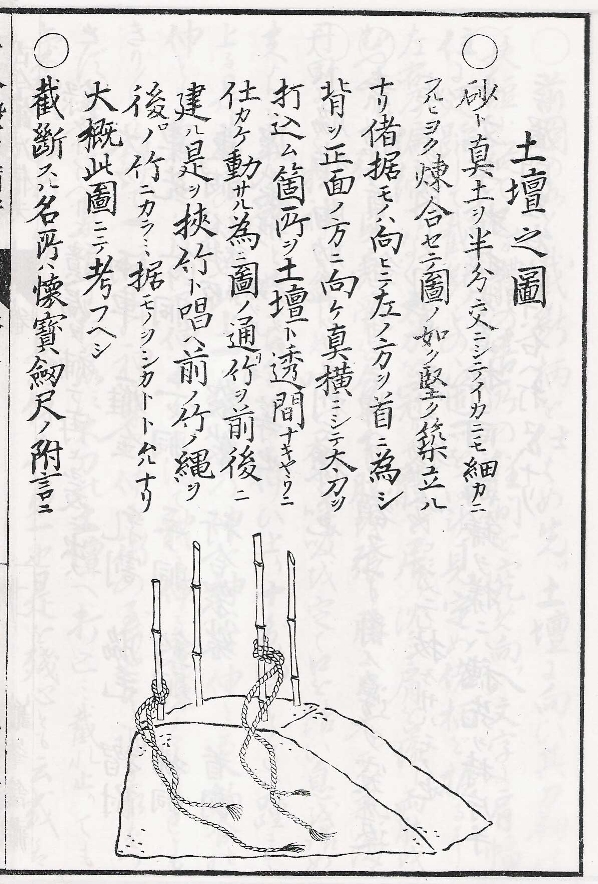

Illustrations of tameshi from Kaihô Kenjaku 懐宝剣尺 (1797) by Yamada Asaemon Yoshitoshi 山田浅右衛門吉利.***

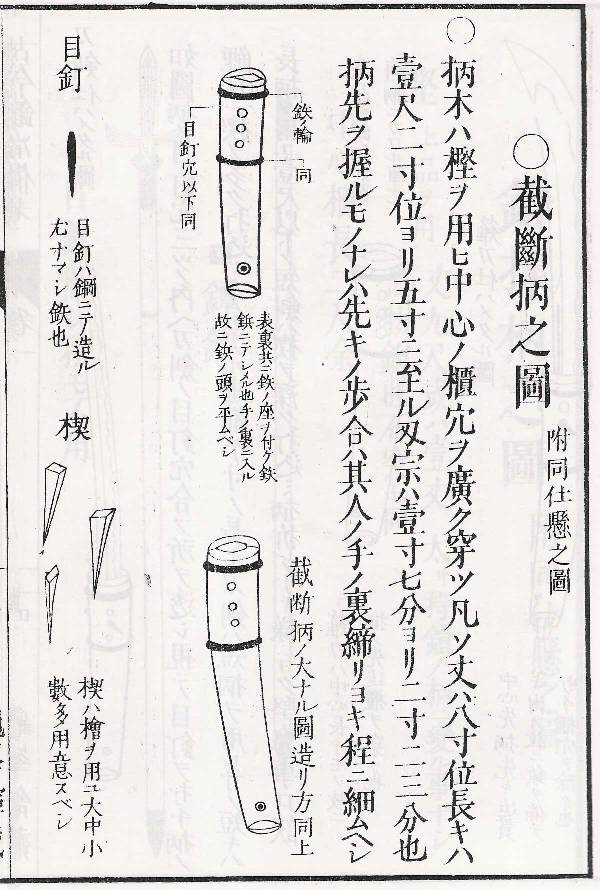

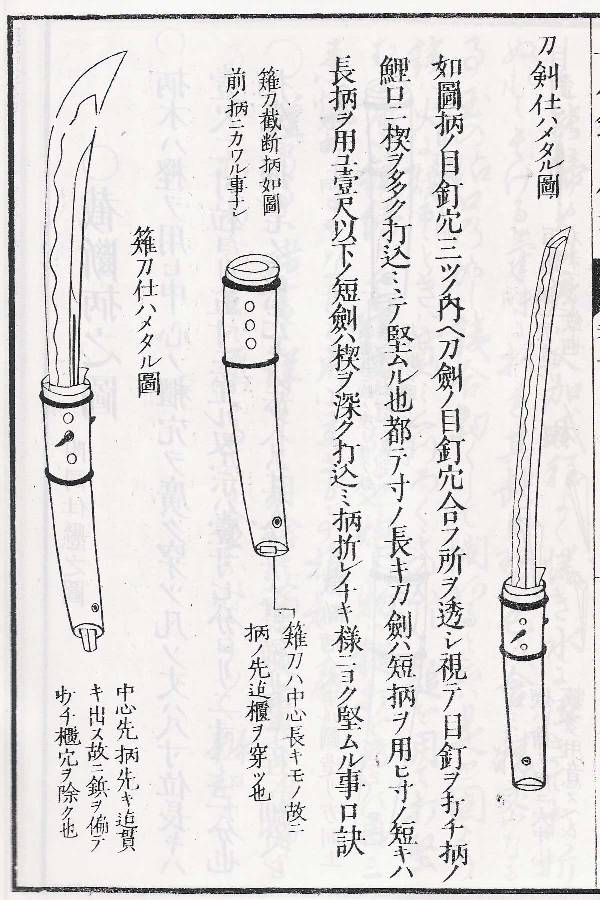

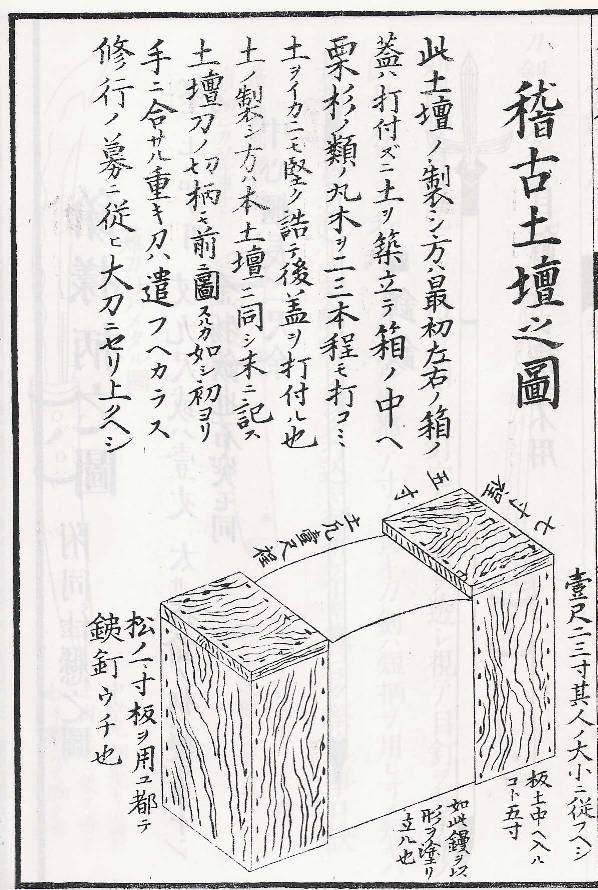

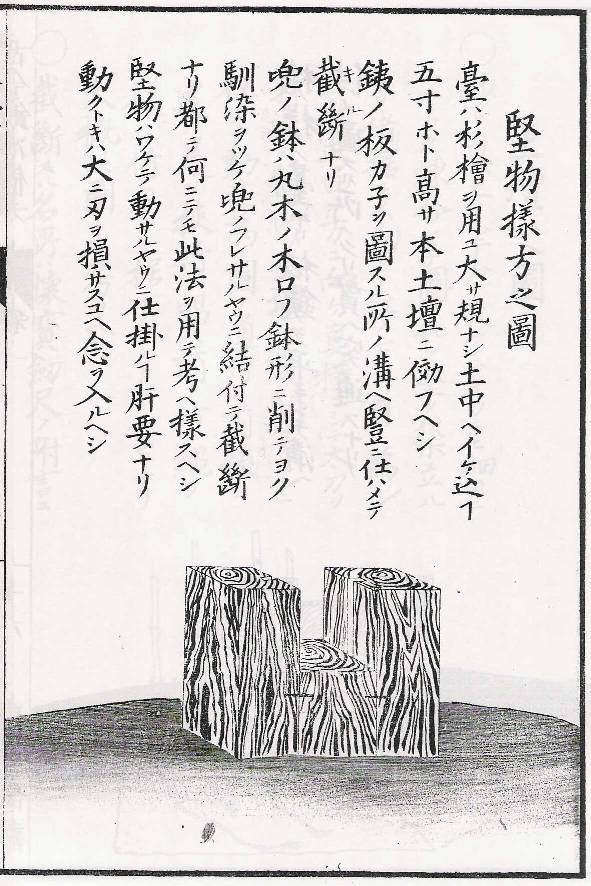

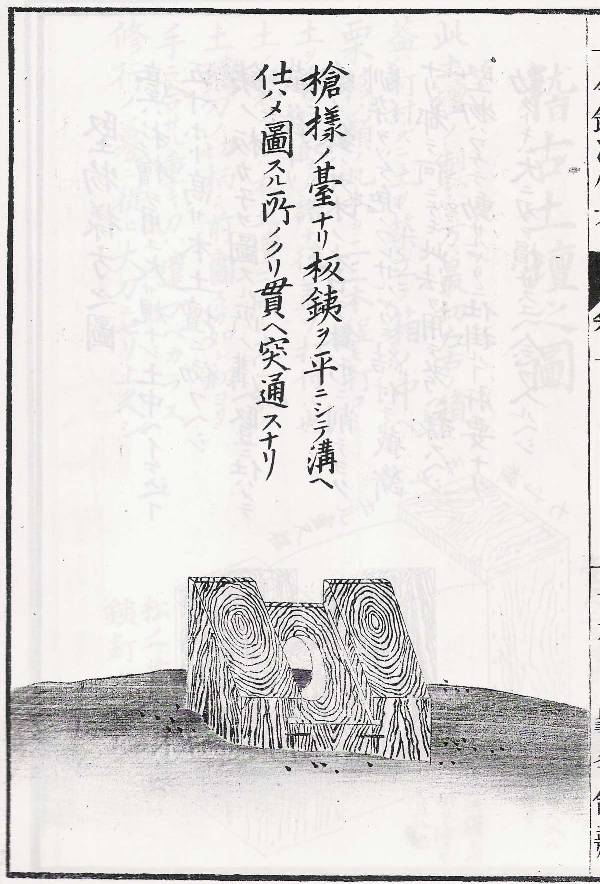

Illustrations of tameshi from Kokon Kaji Bikô 古今鍛治備考 (1830) by Yamada Asaemon Yoshimutsu 山田浅右衛門吉睦.***

**********

*The original article appeared on the old Bugei Sword Forums in June 2003. This version has been edited slightly from the original posts.

** & *** Provided by courtesy of C.U. Guido Schiller

Copyright © by S. Alexander Takeuchi, Ph.D.