|

The

Fascination of Japanese

lacquer Inro

Elliott Long's personal view

Japanese lacquer inro are such incredibly beautiful

works of art, particularly, pieces from the 18th and early 19th

century.

I consider many of them to rate very highly, amongst the finest

treasures of Japan.

With a limited education, my intention is to use and

to explain the terms and names, that are most commonly in use.

This way other collectors who might be tempted to look at sale

catalogues, will be more able to appreciate and understand the

descriptions.

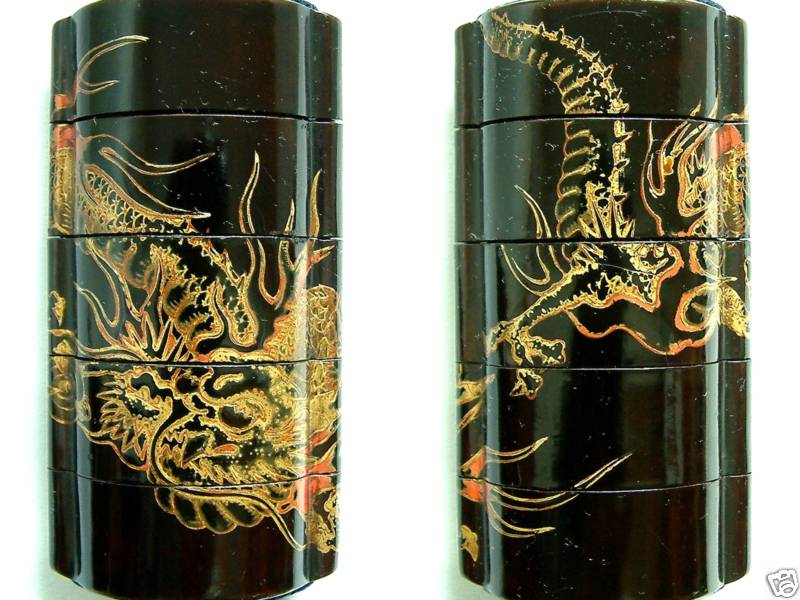

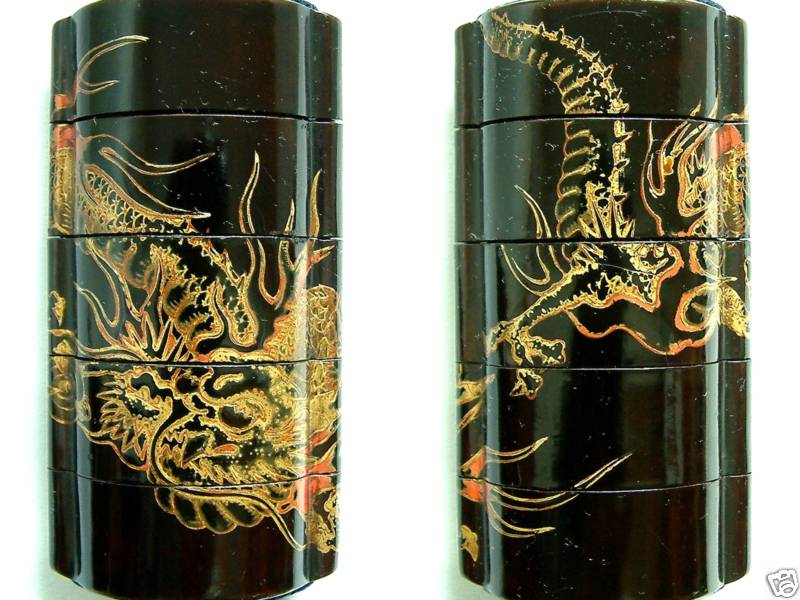

Inro Fashion

With the introduction of the kimono, the 'Inro' became one of

the most important and essential fashion accessories used to carry on

ones person such items as ink seals and medicines. The Kimono had no pockets so the inro was a clever container,

consisting of a number of interlocking small separate sections, all held

together on a silk cord and worn hanging from the sash tied at the

waist. Soon it evolved from a purely functional item to one of very

high fashion, and the designs and decoration gradually became richer,

finer and even more lavish.

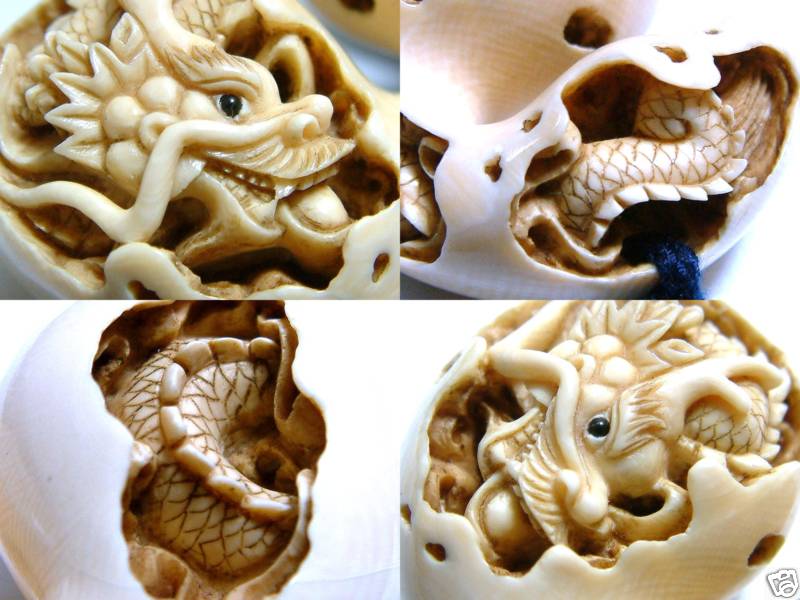

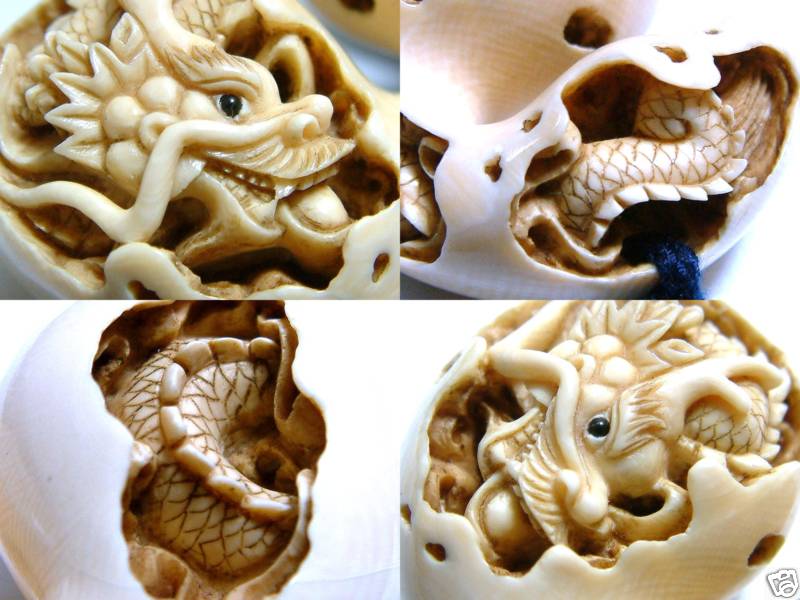

Netsuke and Ojime

A bead known as an 'Ojime' kept the various sections closed tight together.

A toggle normally a small wood or ivory carving known as a 'Netsuke' would also be threaded on to the silk cord.

The netsuke (these are such superb little sculptures) would be pushed up under the sash (known as the

'Obi') that was tied round the waist, and would thus hold the inro hanging below.

The silk cord would have had to be about 56 inches long, and was

threaded in such a way, that about 3 to 4 inches of the cord would show

below the

'Obi' to the 'Ojime' and inro.

Under the inro a many-looped

special bow was formed, with normally six loops all of the same

size.

There would only be one knot and this would be hidden in the

larger of the two cord holes, within the

netsuke.

No loose ends would be visible.

Sometimes a 'Manju' would be used instead of the netsuke.

These are rather like a thick pocket watch shaped carving, comprising

two sections that open up.

The lower piece has a central hole, and an eyelet for the cord

is fixed inside the upper section.

Once attached to the cord, the knot would remain hidden inside

but unlike the

netsuke, the carving or decoration of a manju is only

two-dimensional.

The earliest 'Ojime' were simply a drilled bead, often of coral,

as they had faith in a superstition that coral would disintegrate if

near to poison.

Quite valuable to them, if only it had been true, as they

carried and took some very strange medicines.

Later semiprecious stones and ivory were used, some of them are

beautifully carved, and there are also many very fine metal

ojime.

Today collectors even specialise in just ojime and they have

become quite valuable.

I do think it is rather a shame that so many of these items are

now collected separately, when they really all belong together.

For many years there have been netsuke collectors, and I can

appreciate why, as they are complete artworks, as well as being

wonderful handling pieces.

I always considered myself to be rather a specialist collector,

but I would not be happy to own

inro, without ojime or netsuke, as they would seem so

incomplete!

I could not imagine being satisfied with only collecting the

ojime, beautiful as some of them are.

Obviously these high prices have been the main reason for such

specialisation!

A rare piece from one of Japanís most famous lacquer inro makers.

Care of Lacquer

Antique lacquer, Japanese inro, was always highly valued for its lasting qualities and strength. A very high gloss could be achieved, proving impervious to alcohol, acids and hot liquids. It would also have appealed to the Zen Buddhism ideals of ĎYin and Yangí, as lacquer appears to be so delicately beautiful and light in weight. Yet, it is hard, impermeable and enduring.

However great care still needs to be taken when handling antique Japanese lacquer inro (especially when complete with ojime and a netsuke, or manju) as the inro can so easily be damaged by knocks. The most common cause of damage occurs when an inro is first picked up. If the netsuke, or manju, is allowed to swing and bump into the inro, the lacquer will certainly dent and worse still might chip.

The best and correct way to pick up an inro, is to firstly pick up the netsuke, or manju, then to hold and use the silk cord to turn the inro around to look at the other side when inspecting Inro, rather than to finger the lacquer, as there is something in our perspiration that dulls the shine in time. As an alternative some people only handle lacquer whilst wearing very soft gloves.

All lacquer is best kept in a reasonably humid atmosphere, avoiding any sudden changes of temperature. In some climates this is difficult to arrange, without having good air conditioning. It is also a good idea to keep a bowl, or two, of water where ever the Japanese inro are stored, but even more important to avoid the use of any spot lights within close proximity. Antique Japanese lacquer Inro are such incredibly beautiful works of art, that it is well worth while taking good care of them.

This is a fine Edo period Japanese inro of Takamaki-e. There are 4 sections and the fit is very good at each level. The motif is a Samurai with his attendants. The condition is very good for its age. All of the decoration in raised gold and colored lacquers in high relief on a kinji bright-gold ground is secure. There is some normal use rubbing and wear of some of the tree branches. There is some light residue remaining on the inside bottom corners of some of the compartments probably from medicine or other stored materials. A rare piece from one of Japanís most famous lacquer inro makers.

Compositions in general favoured nature, animals, flowers,

birds, insects, Mount Fuji, every day life, myths and legends.

The first western visitors also fascinated the Japanese.

The Portuguese were the first to arrive in 1542, followed soon by the

Dutch, and all the arts were greatly influenced from the mid 16th

century onwards.

Dutchmen in particular are featured quite frequently in a wide

range of

Asian art.

Amazing Skills

Several craftsmen were involved in the making of an inro.

First the very thin wood base would have been painstakingly made, with

carefully selected wood, where all the knots had to be avoided.

Conifers were preferred as this wood contained very little

resin.

It would then have been handed to the next craftsman, a

specialist at applying the numerous base layers of lacquer.

Each layer would be extremely thin, and gradually finer and

finer quality

lacquer was used, at least 30 layers were applied, so that no

trace of the wood inside could any longer be visible.

Only at this stage would the lacquer artist responsible to

design and create the many layers of decoration begin.

What does seem amazing to me, when one considers how the wood

base was made, was the fact that they would have had to make allowances

for the thickness of all these layers.

Yet the Inro sections fit and slot into each other so perfectly,

that one can hardly see any of the dividing lines once closed.

The Decoration

Often two artists would collaborate to decorate an inro, one a

lacquer artist, the other could be a metal worker or even a

netsuke carver, providing wonderfully worked items, that would

be inlaid in the

lacquer.

Various materials have been used in this way such as precious

metals,

pottery, ivory, shell, horn and many others.

Incidentally, there had to be very close collaboration, for each

time an inlay in the design overlapped more than one section, it had to

be made in two pieces to allow the

inro to open.

Such inro often have two signatures as both of the artists would

sign.

This is a fine Edo period Japanese Hiramaki-e inro. There are 3 sections and the fit is very good at each level. The designs are in hiramaki-e with accents of thin iridescent shells as leaves. The ground is roiro. The condition is very good for its age. It also comes with a finely carved tsuishu bead ojime. The netsuke is deer antler with rooster and aoi leaf with cord attachment. I would assume both these pieces are not original to this inro. The cord has also been replaced.

This is a fine Edo period Japanese inro. There are 3 sections and the fit is very good at each level. The condition is very good for its age. All of the makie decoration is secure. A rare piece from one of Japanís lacquer inro makers.

The Artists

Signatures however, are not always a sure way of knowing who did

the work.

Often the signature was placed in honour, not as a forgery, of a

great artist who originated the design such as the top early artists

Ritsuo and Korin.

Many very fine lacquer works were not signed at all.

Pieces that were commissioned by the Shogun or Daimyo, where only the

highest of standards were acceptable, would not normally be signed, no

matter how important the artist.

In 1868 the Meiji restoration meant the loss of such patrons, and Japan had opened up to the west.

This meant that artists had to try to appeal to new clients, with an unknown western taste.

They were not prepared however, to give up certain of their traditional designs and techniques.

Family names passed down from one generation to another; the

name of a particularly admired artist would be signed by all the

following generations.

They would also have non related students, who would be

encouraged to use the same name, on work of a high enough standard, that

is, until they were sufficiently proficient to become

independent.

One such family name was Koma, where the later very famous 19th

century artist, Shibata Zeshin was taught.

A rare piece from one of Japanís most famous lacquer inro makers.

A rare piece from one of Japanís most famous lacquer inro makers.

If you have a good eye for composition the appreciation of

lacquer work is hard to resist.

On inro they have very ingenious methods of design to make one

wish to see the other side, such as the use of a rope that mysteriously

disappears round the side, or a scroll that flows round the

inro. I do hope that there will always be private collections and that

lacquer will not be confined to Museums, as it is such a fascinating

Japanese art form.

|