A HISTORY OF THE UKIYO-E WOODBLOCK PRINT

As the 16th century drew to a close, an urban middle class emerged

in Edo, capital of the Tokugawa shogunate since 1603, as well as in other major

cities such as Kyoto, Osaka and Sakai. These merchants, artisans and lordless

samurai of low rank (ronin) developed a very special way of life with its own

distinct literature and art, which came to be known as ukiyo. Ukiyo in early Japanese

poetry is the floating, transient, idle world. As originally used in Chinese poetry,

the term is resonant with the pessimism and melancholy of Buddhist philosophy.

By the middle of the 17th century in Japan, it had acquired a new meaning. During

these years ukiyo came to signify the elegant world of stylish pleasures. The

novelist Asai Ryoi provided a definition in his 1661 novel Tales of the Floating

World (Ukiyo-monogatari): "Living only for the moment, savoring the moon,

the snow, the cherry blossoms and the maple leaves, singing songs, loving sake,

women and poetry, letting oneself drift, buoyant and carefree, like a gourd carried

along with the river current."

It is this era as well that witnessed the creation of ukiyo-e, "pictures

of the floating world," the splendid genre painting of the urban middle class.

It is remarkable how this near tidal wave of hedonism could have ushered in

a cultural and artistic current of a strength equal to that of classical Japanese

arts. Yet like the latter traditions ukiyo-e is inherently Japanese.

Thanks to the art of printing, ukiyo novels and images eventually were to find

their way to the citizens. The first publication with woodcut illustrations

in the purely Japanese style of the Tosa school was the 1608 edition of the

Tales of Ise (Ise-monogatari). These illustrations are attributed to the versatile

Honami Koetsu, who designed the calligraphic models for the type, which was

partly movable.

This publication became a model for commercial book production in the urban

centers.

Around

the middle of the 17th century, a new ukiyo literature and imagery began to

enter the book market. Featuring heroes modeled on city dwellers, this new line

celebrated the stylish diversions of urban pleasure districts, the theater, festivals

and travels. Guidebooks were also popular, and illustrated what was considered

worth seeing in both town and countryside.

Around

the middle of the 17th century, a new ukiyo literature and imagery began to

enter the book market. Featuring heroes modeled on city dwellers, this new line

celebrated the stylish diversions of urban pleasure districts, the theater, festivals

and travels. Guidebooks were also popular, and illustrated what was considered

worth seeing in both town and countryside.

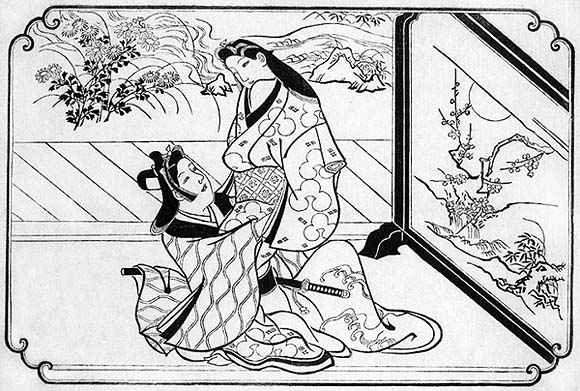

Around 1670, there appeared works by the first ukiyo-e master from Edo whose

name has been recorded: Hishikawa Moronobu. Moronobu shaped the graphic style

of the printed picture. Like almost all other subsequent woodcut artists, he

also worked in polychrome painting. Although woodcuts came to have their own

distinctive style, it was one nourished by fashion and novelty. Thriving on

what was in vogue and on the latest ideas, the woodblock print possessed its

own formal aesthetic and had no spiritual relationship with trends in classical

painting. From decade to decade, changes in ukiyo-e subjects and drawing styles

were largely a function of the changing technology of printing.

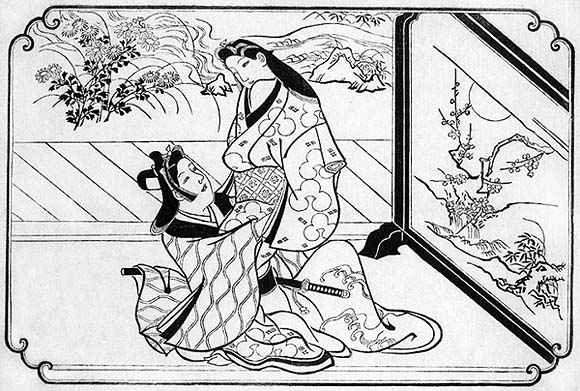

Specialisation

evolved as one artist devoted himself to pillow pictures, another concentrated

on pictures of women and nature while a third satirised fashions and others

developed the style of theatre prints..

Specialisation

evolved as one artist devoted himself to pillow pictures, another concentrated

on pictures of women and nature while a third satirised fashions and others

developed the style of theatre prints..

In Edo, Masanobu and in Kyoto, Sukenobu were using flowing, expressive brushwork

in woodcuts to depict not only women of all classes, but also a range of historical

and vernacular subjects. Powerful and of great force, these pictures are drawn

with tremendous precision and reveal the hands of painters indifferent to the

limitations of the new printmaking technique. Between 1711 and 1785 the first

perspective pictures (uki-e) were also put on the market by Masanobu, who experimented

with Western-style receding perspective in woodblock prints.

In 1741-42, the first two-color prints as single-sheet woodcuts were issued.

A technique of rapid printing was developed by the publisher Emiya for use in

prints based on several blocks; it employed registration marks (kento) to insure

the accuracy ot the final image.

The artistic challenge of the new technology was met initially by Suzuki Harunobu

with his calendar prints of 1764-65. Katsukawa Shunsho, a contemporary of Harunobu.

became a drawer of woodblock prints only in his later years. From 1767 on, his

portraits of actors (nigao-e) were successfully drawn from live models on stage.

While in the time of the Torii masters, portraits of actors bore names and descriptions

identifying only stereotypical figures, Shunsho and Mori Buncho no longer required

such appellations as the actors they portrayed were recognisable in face and

figure.

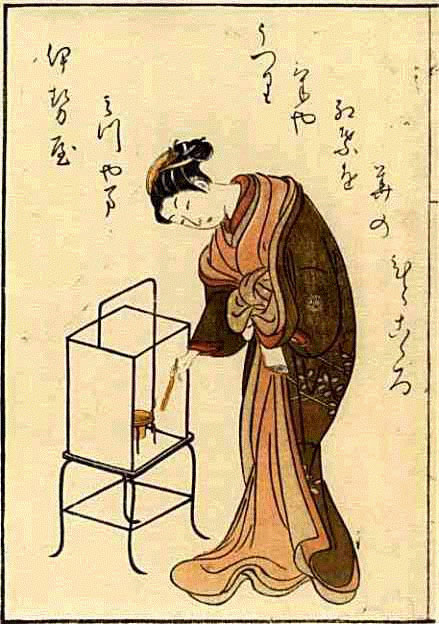

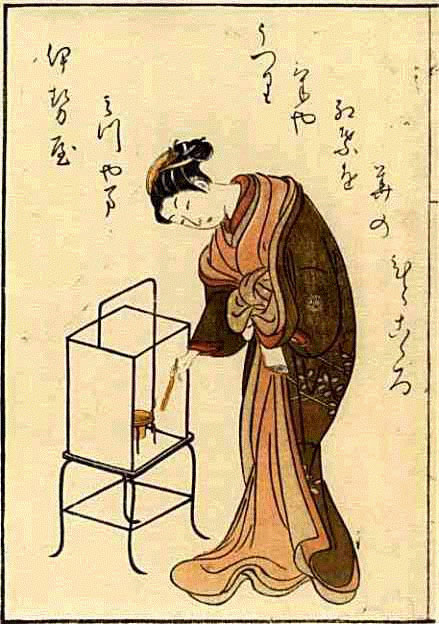

During the 1770s, Isoda Koryusai, a student of Harunobu, initiated an austere

type of courtesan portraiture with realistic proportions. In his sequence of

young courtesans in designer dresses, he, in fact, established models for fashion

in the world of elegance; for it was at this time that even ladies began to

dress themselves according to the latest whim in the vogues of the Yoshiwara.

Koryusai

portrayed women as well as animals and plants, but only rarely depicted actors.

It was with his work that the woodblock print achieved its "classic style,"

for his figures appear to be alive, despite the fact that, like other woodcut

artists of his day, he had probably never engaged in anatomical studies. He

used models from the world of the lower middle classes, transposing them into

an idealized sphere of aristocratic elegance and beauty.

Koryusai

portrayed women as well as animals and plants, but only rarely depicted actors.

It was with his work that the woodblock print achieved its "classic style,"

for his figures appear to be alive, despite the fact that, like other woodcut

artists of his day, he had probably never engaged in anatomical studies. He

used models from the world of the lower middle classes, transposing them into

an idealized sphere of aristocratic elegance and beauty.

Toshusai Sharaku's portraits of actors truly succeed, for the first time, in

portraying a subject's distinctive inner character. Around the same time, with

great formal economy, Utamaro also created intensely expressive portraits of

women. The unsurpassed quality of prints from 1780 to 1797 is due, for the most

part, to the publisher Tsutaya Jusaburo, who held a magnetic attraction for

the outstanding artists of his day. With Utamaro, nature prints came to life

again. After 1780, he drew detailed insects, shells and birds for luxury editions

of haiku anthologies. Demonstrating a talent for intent observation of nature,

his pictures of plants and animals contrast markedly with the conventional designs

of Koryusai. Strict anti-luxury laws introduced by the Shogun in 1790, limited

previous liberties with regard to playful experimentation and alteration of

stylistic conventions.

The

pivotal point in the art of ukiyo-e came with Katsushika Hokusai, "the

one obsessed with painting". He conclusively shifted the emphasis from

personal portraiture to a depiction of nature. People in his pictures were unintentionally

comic creatures going about their daily business. Hokusai began by creating

landscapes in the spirit of ancient Japanese art; he went on to attain a new

vision of nature. He was fascinated with European copperplate engraving, a technique

which he had encountered in his studies. Through color shading and depth perspective,

he strove for a new spatial reality. The results were strange, surrealistic

creations of the imagination, which he soon surpassed. When more than sixty

years old, Hokusai discovered a new kind of landscape drawing. Around 1831,

he began to publish his "Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji" (Fugaku sanjurokkei),.

his world-famous series of woodcuts. By this point, he was no longer copying

but was instead achieving a complete freedom of stylistic means, drawing on

Japanese, Chinese and European art.

The

pivotal point in the art of ukiyo-e came with Katsushika Hokusai, "the

one obsessed with painting". He conclusively shifted the emphasis from

personal portraiture to a depiction of nature. People in his pictures were unintentionally

comic creatures going about their daily business. Hokusai began by creating

landscapes in the spirit of ancient Japanese art; he went on to attain a new

vision of nature. He was fascinated with European copperplate engraving, a technique

which he had encountered in his studies. Through color shading and depth perspective,

he strove for a new spatial reality. The results were strange, surrealistic

creations of the imagination, which he soon surpassed. When more than sixty

years old, Hokusai discovered a new kind of landscape drawing. Around 1831,

he began to publish his "Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji" (Fugaku sanjurokkei),.

his world-famous series of woodcuts. By this point, he was no longer copying

but was instead achieving a complete freedom of stylistic means, drawing on

Japanese, Chinese and European art.

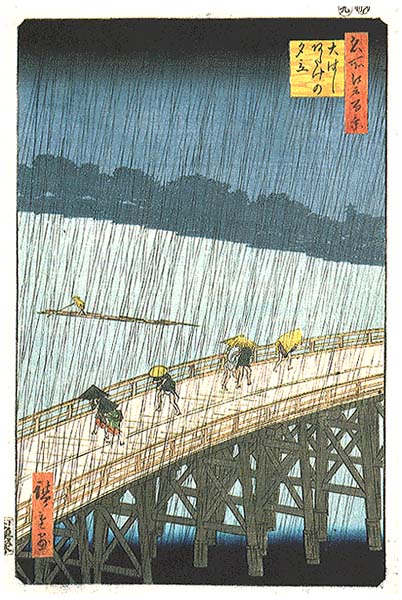

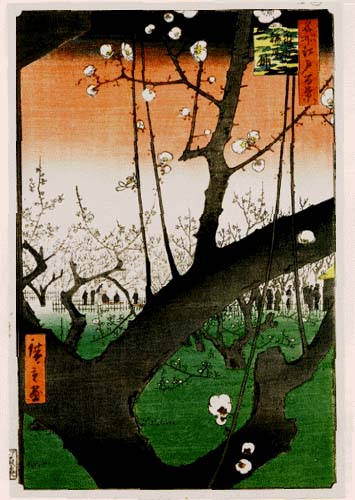

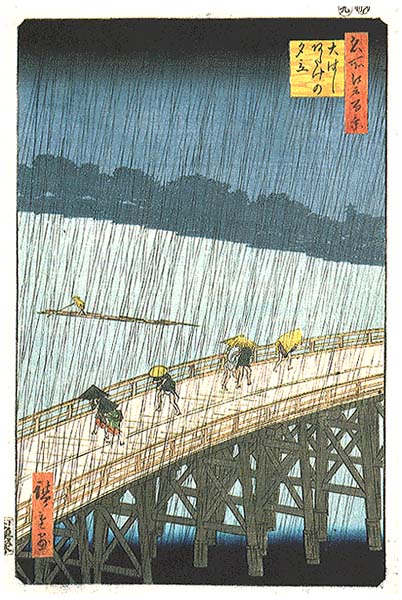

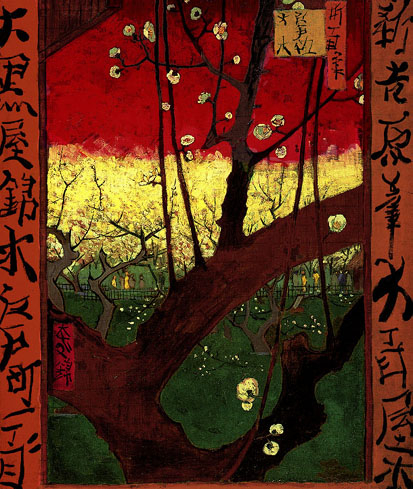

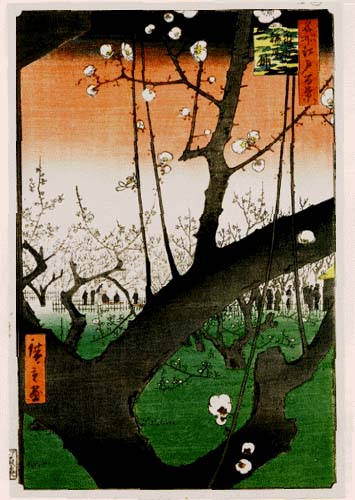

Within a decade, Hokusai was to be surpassed as a landscape painter by Ando

Hiroshige, who drew from nature. Following a journey along the Tokaido highway

in 1832, Hiroshige portrayed the familiar environment of Edo and of Kamigata

to the south. In this series, he revived the familiar territory of travel guides,

representing stops along the way by means of painterly woodblock prints. Particular

moods of the seasons, weather and time of day lend his landscapes a convincing

closeness to nature. Kunisada and Kuniyoshi were his

contemporaries in Edo. Kunisada for the most part used a highly conventional

style, although his prints find many admirers nowadays, due to their striking

posterlike coloring. In a series of surimono from the 1820s, dedicated exclusively

to actors of the Ichikawa family, particularly Ichikawa Danjuro VII (1791-1858),

Kunisada also demonstrated his capacity for more original designs. On the other

hand, his contemporary and classmate, Kuniyoshi, became a great, courageous

artist, displaying humor and a quality of generosity throughout his work.

His masterful depictions of the hero and landscapes intermingled

European and Chinese formal conventions to explore the limits of graphic power,

perspective, and the effects of light and shadow.

In 1842, as part of the Tempo reforms, pictures of courtesans, geisha and actors

were banned, marking the demise of a subject matter that had already fallen

from favour. Although both the Yoshiwara and illustrations of the courtesans

experienced a revival after the period of the Tempo reforms, neither reached

their earlier peaks of refinement. The social and political upheaval that characterised

nineteenth-century Japan saw a change in artistic taste and direction that would

relegate images of elegant Yoshiwara beauties to the distant past.

During the Kaei era (1848-1854), many foreign ships came to Japan. It was a

period of unrest, a state of affairs reflected in the ukiyo-e of the time. Numerous

pictures and caricatures were produced which alluded to the current situation

in the country. Following the Meiji restoration in 1868, all kinds of cultural

imports came to Japan from the West, photography and printing techniques being

received with particular enthusiasm. As a result, the art of ukiyo-e went into

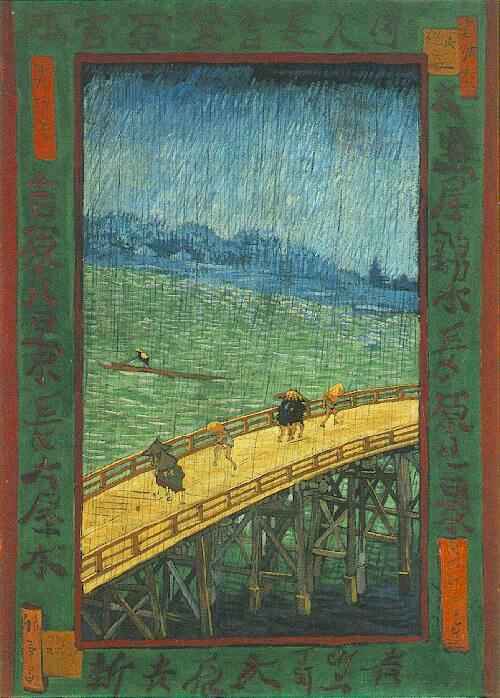

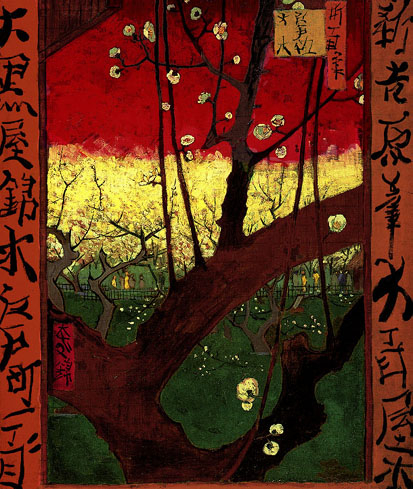

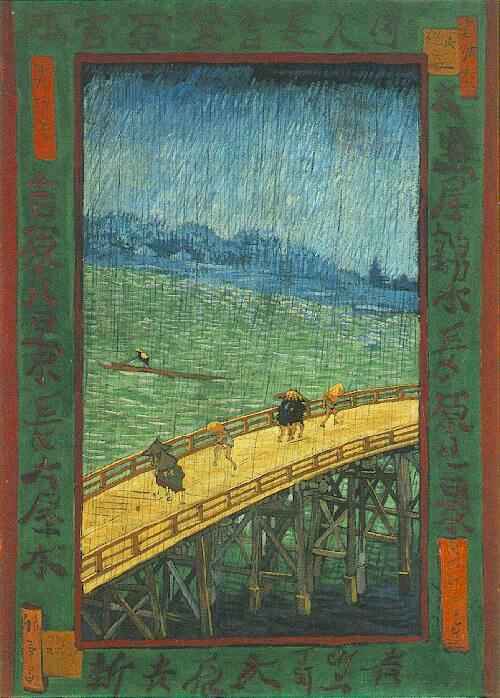

decline in Japan. Its influence on European art was however dramatic. Van Gogh,

for example, paid Hiroshige the compliment of imitation.

Ukiyo-e is an art form with a history spanning more than three centuries. It

developed as the middle classes own form of cultural expression, and is unique

in the world. In the course of time, the style of ukiyo-e naturally underwent

changes, as did the lives of the people with which these woodblock prints were

closely linked. But from Japan they have travelled the world; unbeknown to their

creators, ukiyo-e have had a profound influence on modern Western painting.

With this in mind, we can still appreciate their great vitality today.

Around

the middle of the 17th century, a new ukiyo literature and imagery began to

enter the book market. Featuring heroes modeled on city dwellers, this new line

celebrated the stylish diversions of urban pleasure districts, the theater, festivals

and travels. Guidebooks were also popular, and illustrated what was considered

worth seeing in both town and countryside.

Around

the middle of the 17th century, a new ukiyo literature and imagery began to

enter the book market. Featuring heroes modeled on city dwellers, this new line

celebrated the stylish diversions of urban pleasure districts, the theater, festivals

and travels. Guidebooks were also popular, and illustrated what was considered

worth seeing in both town and countryside.  Specialisation

evolved as one artist devoted himself to pillow pictures, another concentrated

on pictures of women and nature while a third satirised fashions and others

developed the style of theatre prints..

Specialisation

evolved as one artist devoted himself to pillow pictures, another concentrated

on pictures of women and nature while a third satirised fashions and others

developed the style of theatre prints.. Koryusai

portrayed women as well as animals and plants, but only rarely depicted actors.

It was with his work that the woodblock print achieved its "classic style,"

for his figures appear to be alive, despite the fact that, like other woodcut

artists of his day, he had probably never engaged in anatomical studies. He

used models from the world of the lower middle classes, transposing them into

an idealized sphere of aristocratic elegance and beauty.

Koryusai

portrayed women as well as animals and plants, but only rarely depicted actors.

It was with his work that the woodblock print achieved its "classic style,"

for his figures appear to be alive, despite the fact that, like other woodcut

artists of his day, he had probably never engaged in anatomical studies. He

used models from the world of the lower middle classes, transposing them into

an idealized sphere of aristocratic elegance and beauty.  The

pivotal point in the art of ukiyo-e came with Katsushika Hokusai, "the

one obsessed with painting". He conclusively shifted the emphasis from

personal portraiture to a depiction of nature. People in his pictures were unintentionally

comic creatures going about their daily business. Hokusai began by creating

landscapes in the spirit of ancient Japanese art; he went on to attain a new

vision of nature. He was fascinated with European copperplate engraving, a technique

which he had encountered in his studies. Through color shading and depth perspective,

he strove for a new spatial reality. The results were strange, surrealistic

creations of the imagination, which he soon surpassed. When more than sixty

years old, Hokusai discovered a new kind of landscape drawing. Around 1831,

he began to publish his "Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji" (Fugaku sanjurokkei),.

his world-famous series of woodcuts. By this point, he was no longer copying

but was instead achieving a complete freedom of stylistic means, drawing on

Japanese, Chinese and European art.

The

pivotal point in the art of ukiyo-e came with Katsushika Hokusai, "the

one obsessed with painting". He conclusively shifted the emphasis from

personal portraiture to a depiction of nature. People in his pictures were unintentionally

comic creatures going about their daily business. Hokusai began by creating

landscapes in the spirit of ancient Japanese art; he went on to attain a new

vision of nature. He was fascinated with European copperplate engraving, a technique

which he had encountered in his studies. Through color shading and depth perspective,

he strove for a new spatial reality. The results were strange, surrealistic

creations of the imagination, which he soon surpassed. When more than sixty

years old, Hokusai discovered a new kind of landscape drawing. Around 1831,

he began to publish his "Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji" (Fugaku sanjurokkei),.

his world-famous series of woodcuts. By this point, he was no longer copying

but was instead achieving a complete freedom of stylistic means, drawing on

Japanese, Chinese and European art.