= Japanese Names =

The first thing that needs to be

remembered about Japanese names is that the surname comes first. The first

Ashikaga shôgun, Takauji,

was thus Ashikaga Takauji, not Takauji

Ashikaga, despite the order sometimes given his name in many Western books. It

is a modern oddity that even today the names of Japanese, when appearing in

English, are often reversed (perhaps it looks foreign and therefore more

impressive to them?) and written in the correct order when using kanji. This

is a trend slowly being reversed by magazines and newspapers in

Another thing to keep in mind is

that Japanese is written with what some may consider ideographs or pictographs;

every element has not only a sound but a meaning. Consider the modern English

names Heather, Holly,

Even ancient names have meanings

that can be understood if one knows the original language. They are just names,

however. Just as a girl named Rose is not a flower, a man named Takeshi need

not be brave, nor would a woman named O-gin actually be made of silver.

Japanese names are not random

syllables strung together. Even today, where there is a habit to have girls’

names written in the kana syllabary rather

than the ideogrammatic kanji, some will say

“Oh, it doesn’t have a kanji,” when in point of fact, if it is a word,

there is a kanji — they merely may not have thought of which of the

synonymous kanji it might be.

This being said,

let us take a look at names.

Structure

The structure of names changed

considerably over the nearly 1,500-some years of recorded Japanese history.

During the Heian and early

Those appointed governors of

provinces would insert their title between sur- and

given names. Hideyoshi, after he was made nominal

governor of Chikuzen, was styled “Hashiba

Chikuzen-no-kami Hideyoshi.”

In SCA parameters, this should work well for landed barons of Japanese

extraction; for example, the founding baron of the Trimarian

barony of An Crosaire (meaning “The Crossroads” and

rendered into Japanese as “Kiro”) would have been

Sakura Kiro-no-kami Tetsuo. This is also one reason

why I strongly feel that the use of “Naninani-no-kami”

for “Lord Whatever” should be disallowed. It was and is quite clearly a landed

title, even though often used only honorarily. (By

the way, “naninani” is the Japanese

equivalent of “whatever” or “such-and-such.”)

Later, in the Momoyama

and

Surnames

Surnames (myôji)

were the prerogative of the aristocracy, whether civil or military. Commoners

did not bear surnames until the Meiji Restoration.

Quite a few surnames were for

descriptive reasons. The founder of the Fujiwara clan, a man originally named Nakatomi no Kamako, received his

new name from the field (in Japanese “hara/wara”)

of wisteria (

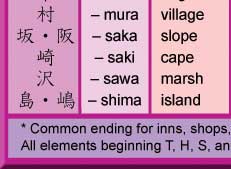

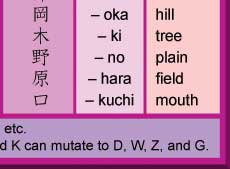

Many surnames are clearly

geographical or point to a physical property. Usually such descriptive names

with kanji AB means B of [the] A. For example, Yama·moto (= base of the

mountain), Ta·naka (= center of the paddy), Naka·da (= middle paddy), Shima·mura (= island village), Hon·da

(= original paddy), Ki·no·shita (= under

the tree) etc.

Let’s take a look at ta/da (= rice paddy)

as an example. Quite a few specify a plant or tree nearby to delineate the

exact area: Takeda (= bamboo paddy), Fujita (= wisteria paddy), Matsuda (= pine paddy), etc. Others are location specific (Shimoda, lower paddy), possessive (= Murata, village paddy), or some other descriptive (Furuta, old paddy.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

As only samurai and the aristocracy

had true surnames, everyone else was primarily denoted by what he did for a

living or where he lived; Yaoya was the greengrocer. Yamanoue was the guy who lived on top of the mountain. Such

a man would be styled as Komeya no Toku, “Toku the rice merchant.”

In this, the names were similar to those of the aristocracy, and (e.g., if

there were a nobleman whose surname was Yamanoue), it

could have been confusing. In this more modern instance, the “no” would

be the giveaway; it literally means “of”

One form of “surname” typical among

commoners also occurred; the appellation. These are nicknames, like Ethelred

“the Unready” or Charles “the Bald.” They are called “

The vast majority of surnames

consist of two kanji; a few names use three or more, and there is a

handful of one kanji names as well. Some of the latter — though by no

means all, as such native Japanese names as Katsura, Minamoto, and Kusunoki show —

point to possible Chinese or Korean ancestry, where single-kanji

surnames are the rule. It has been estimated that there are some 1,300 – 1,400

possible kanji used in the initial position in surnames, but only some

100 commonly occur in the final.

|

Some

surnames of families active prior to 1600 |

||||

|

Abe |

Hoshina |

Kô |

Nishi |

Soga |

|

Surnames

of kuge families |

|||

|

Anenokoji |

Hirohashi |

Kazan’in |

Rokkaku |

Those in the SCA who deliberately

choose their persona to be not of the aristocracy or samurai class need

to have a locational descriptive, job title, or adana rather than a true surname, as only the upper

classes had surnames.

Those desiring to simply identify

themselves as being of a particular place will make use of the “no”

particle. The form, given a man who, in English, would be named Jirô of Mutsu, would be Mutsu no Jirô. Remember that the

rule is, the “possessor” — or larger element — comes first; in this case, the

“Surnames” of the Buddhist clergy

had special rules, so those desiring to be monks or such should pick a temple

to be from (e.g.; ”Enryakuji

no Tosabô,” meaning Tosabô

[= a monk from Tosa] of

Given names: men

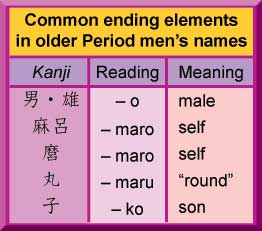

Up until the seventh century, many

names for men of the upper classes — and this is pretty much all we have on

record — often ended in ~maro or ~ko

(e.g.; Muchimaro, Nakamaro,

Kamako, etc.). Their names generally reflected their

characteristics, or their background. In post-Nara years, naming patterns would

change; partly influenced by the Chinese system, partly influenced by

Yômyô

The most common type of name for

children was the yômyô (or dômyô)

— specifically a child’s name — which was conferred with due ceremony six days

after birth. This name usually ended with the suffix ~maru,

~maro (written either with one or two kanji

that have the same pronunciation), ~o, or ~waka.

Occasionally, there would be similarities to the names of adults of the Nara

Period.

~Maru/maro

is a suffix denoting affection, and often appears on the names given swords, as

well. It survives today in the naming of ships; virtually all non-military

vessels in

Another naming habit was taking

positive character traits — adjectives or verbs — and making them names.

Examples are names like Takeshi (= brave), Manabu (= study), and

Susumu (= go forward). Those of the lower classes kept these names all

their lives. What this does is point to the plebeian origins of names such as

Takao, Hideo, and all of the other names making use of the noun or adjective

element and the “male” suffix ~o. It also indicates that such names would not

likely be acceptable for any but late-Period usage for those in upper classes.

Zokumyô

The

zokumyô, (confusingly enough also

called tsûshô, kemyô,

or yobina) generally reflected the

numerical order of birth the child had in the family. This name was taken upon

the genpuku (coming of age) ceremony, and was

the one by which men were commonly known to their close friends and family

members. The numerical order names were often altered in some way with the

addition of an auspicious adjective before it, such as Dai~ (big), Chô~ (long), Ryô~ (good), or

something similar. In Heian

The

zokumyô, (confusingly enough also

called tsûshô, kemyô,

or yobina) generally reflected the

numerical order of birth the child had in the family. This name was taken upon

the genpuku (coming of age) ceremony, and was

the one by which men were commonly known to their close friends and family

members. The numerical order names were often altered in some way with the

addition of an auspicious adjective before it, such as Dai~ (big), Chô~ (long), Ryô~ (good), or

something similar. In Heian

All things considered, this name

structure produced examples like Daigorô (= big

fifth son), and Chôzaburô (= long third son; the

S here mutating to Z), etc. To simplify things, in the late 1500s

some people started leaving off the ~rô, especially

with first sons. This left names like Ryûzô

(= dragon third), Genpachi (= original

eighth), and Ryôichi (= good first).

Often one might bear a name like “Saburôjirô” — implying that he was the second son (jirô) of a third son (saburô). If

he was the third son of a third son, his name might be “Matasaburô”

— “mata” meaning “again.”

The late great actor Mifune Toshirô has a name taking

the form of a classic zokumyô. Admiral

Yamamoto Isoroku, of

Names ending in ~suke or~nosuke (actually, either

element was written with a variety of kanji), ~emon,

or ~zaemon, though historical-sounding and

aristocratic as they are, are in large part post-Period, as they came from a

habit of naming people after titles (~suke was deputy

governor, and ~emon was a guard title). There were a

few famous people in the sengoku period who bore such names, but the fashion really took off in the

Members of the upper or privileged

classes would have both a zokumyô and a nanori (see below).

Nanori

The formal adult name, taken along

with the zokumyô at the genpuku

ceremony, was called nanori (or jitsumei, “true name”). It usually consisted of two kanji

(very, very rarely more; hardly ever one) producing a four syllable name —

pronounced with the Japanese reading of the characters — which had auspicious

or otherwise positive tones.

After the tenth century, the

practice of the father or godfather (that is, the genpuku

sponsor) granting one of the kanji in his name to the young man during

the genpuku ceremony began; this is why so

many of the Ashikaga shôgun have Yoshi~ as the first element in their names, and the

Tokugawa family Ie~. Looking through a book of

Japanese names or an encyclopedia will show many occurrences of kanji

repetition in a single family. In the Minamoto, there

was Yori~ and Yoshi~: Yoritomo, Yorinobu, Yorimasa, etc.; Yoshitsune, Yoshiie, Yoshichika, Yoshinaka, etc. The Oda clan used

Nobu~ frequently, and the Hôjô

regents used Toki~. (This is one reason the Laurel Sovereign of Arms may wish

to consider allowing the names of exalted families but restrict any using given

name elements common to those clans.)

The order of kanji placement

could have gone either way, but one given a kanji which is first in his

godfather’s name seldom puts it second in his; one could, however, be given the

second kanji instead. This would have been no slight, either; different

families followed different traditions, and different kanji have

different meanings. Yasunobu and Nobuyasu,

written with the same two kanji, merely transposed, are both perfectly

acceptable names.

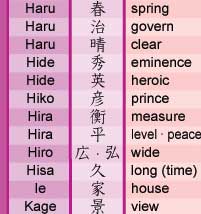

The chart below provides the

principal kanji for the most common elements used in nanori.

As many name elements have different meanings, depending on the kanji used, it

is difficult to provide a complete list of choices. I have only provided a few of

the most common. The chart will enable you to produce thousands of combinations

of nanori.

Keep in mind that the “meanings”

are only cursory at best — few name kanji parse one-to-one with an

English concept, especially when that kanji is being used as a name. For

example, most words dealing with “law” relate to Buddhist concepts of order and

so forth; and the second kanji for “Toshi”

below can be roughly translated as ”agile, alert, ” etc., but it pehaps most closely resembles the English concept “on the

ball.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nanori consisting of a single kanji are either read with the Chinese

pronunciation and sounding monosyllabic to Western ears though in actuality two

syllables (e.g.; actor Matsudaira Ken); or the

Japanese pronunciation utilizing verbal or adjectival forms and are

tri-syllabic (e.g.; Takeshi, brave; Tadashi, correct; Shigeru, luxuriant). On

the whole, such names seem more modern, as they are more common today than in

days past.

Azana

Given names of two kanji,

when read in the Chinese fashion (with Japanese version of the Chinese

pronunciation), are more formal-sounding, and lend an academic, cultured (and,

yes, often clerical) feel to the name. Such names are called azana. Often they are usually indicative of artists,

performers, or men of letters. They are not unlike a medieval man named Karl

living in

Putting it all together

Taking Yoshitsune

as our example, his myôji was Minamoto, his yômyô was Ushiwakamaru, his zokumyô Kurô, his nanori Yoshitsune, and an azana

would be Gikei. All this for a name which should be

registered in the SCA as Minamoto no Kurô Yoshitsune.

The chart above provides enough

fodder for making several hundred names in Japanese. Another way is to look

through a name encyclopædia (the most accessible in

English is probably P.G. O’Neill’s Japanese Names, finally available in

paperback from Weatherhill, or Lady Solveig Thorardottir’s Jinmei chimei techô, a catalogue of names). The only problem here is

that unless you speak Japanese, there is often no telling what the names mean

or if they are Period or acceptable; O’Neill and others suffer greatly for

this, although Jinmei chimei

techô breaks down names by the meaning of the

principal kanji element and provides a date for at least one occurrence

for each name.

Given names: women

A warning on women’s names needs to

be given before anything else is done.

Most of the “names” of women known

in early

It should be remembered that few women’s

names of the Heian Period have come down to us save

those of empresses or the like; other women’s names never made it into the

early genealogical charts.

Women did not change their names as

did the men upon reaching a certain age; they kept theirs for life. The only

likely time a woman would change it would be if, say, she became a nun. Their

names were usually written in kana rather than kanji; the latter

were generally reserved for men, though there is nothing wrong with using them

for a woman’s name. Kana were (and still are) just assumed to be more

feminine.

Although it is often assumed that

all Japanese women’s names end in ~ko,

this is not the case. Historically, very few women had the ~ko ending on their names. (It was originally a male

naming element, in fact.) Women of the highest ranks had it from the Heian Period onwards, but rarely. As late as the 1880s,

only three percent of Japanese women had ~ko

names. By the 1930s, for various reasons, it was around eighty percent. For

Period usage, we in the SCA use it far too much.

Almost completely neglected are

other ending elements (~e and ~yo) or names with no

suffix at all. (Women with ~ko

would in fact often use their names without the ~ko

in Period, recognizing it as an honorable suffix; this usage is no longer the

case, however.) In the court, names ending in ~ko

were actually apparently often pronounced in the Chinese fashion (~shi), so the name of the imperial consort commonly read “Sadako” today was in the court known as “Teishi.”

An interesting note is that names

of more than two syllables were never finished off with a ~ko suffix; it was deemed simply too much name. Women

were usually given two syllable names as well, without the suffix, although in

the court three syllable names (no suffix) were not uncommon.

Frequently

the names of plants, things from the arts, seasonal elements, and other

“feminine” things were taken for use as women’s names. For example, in the film

Ran, the bitch-figure is Kaede (maple). The

1500s saw the introduction of the honorific prefix O~, thus names like O-matsu (pine), O-gin (silver; final n being a

syllable in Japanese), O-haru (spring), etc. Modern

naming practice would render that last as “Haruko.”

Frequently

the names of plants, things from the arts, seasonal elements, and other

“feminine” things were taken for use as women’s names. For example, in the film

Ran, the bitch-figure is Kaede (maple). The

1500s saw the introduction of the honorific prefix O~, thus names like O-matsu (pine), O-gin (silver; final n being a

syllable in Japanese), O-haru (spring), etc. Modern

naming practice would render that last as “Haruko.”

Common second-characters for

women’s names were ~e (branch), ~e (bay), ~e (a great amount of ~), ~no (plain,

field) and ~yo (age, generation), and even the lowly

~me (woman).

Women of noble families — take O-matsu, daughter of Takeda Shingen,

for example — when addressed, would typically be called Matsu-hime. The “-hime” means

essentially princess (and indeed is an address for one), but in rule of use it

functions similarly to the SCA use of “Lady.” She would generally not be called

“O-matsu-hime,” as that might be considered an

incongruous and redundant combination of honorifics.

Taken names

Japanese seem inordinately fond of

pseudonyms.

While it is not uncommon for an

entertainer in the West to take a new name upon mounting the stage, it is an

extreme rarity for a Japanese not to do so. Just about every field of endeavor

has alternate naming traditions.

Men interested in clerical personae

or the Buddhist militant clergy should note that that up until the 1500s, monks

generally took as their “given name” the region they were born, and added to it

the suffix ~bô (= or monk), thereby very Buddhistically severing their ties; they no longer had

names. Musashibô Benkei was

such; he came from the Musashi region (as did a

certain famous swordsman several centuries later) and his chosen name was Benkei. Alternatively, they could add a Chinese-pronounced

name called a hômyô (= Dharma name)

related to Buddhist doctrine or teaching. The lay nobility kept their family

names, and merely adopted Chinese-pronounced hômyô

(e.g.; Takeda Shingen, whose original name was Harunobu, and Hôjô Sôun, whose was Nagauji).

Buddhist names may be followed by

the epithet nyûdô (”one who has entered into

the way”). An example would be Raizen Nyûdô; the usage is really not too dissimilar to “Brother

So-and-so” or “Father So-and-so.” Nyûdô,

unlike traditional monastic clergy, were “lay clergy” — though they lived a

monastic life (at least in theory), they typically had

their own homes and lives. For this reason, “nyûdô”

is often translated as “lay monk.” Shingen and Kenshin were both Nyûdô,

as was Taira no Kiyomori,

the patriarch of the Taira clan at the start of the Genpei War. The concept of “lay monk” was strictly male:

women who became monastics (”ama”

— nun) simply became monastics, regardless of their

actual living conditions.

Names taken by artists and members

of the literati were collectively called azana.

Warriors took gô, painters took gamyô, haiku artists took haimyô,

entertainers geimyô,

etc. The implication behind the new name is that the artist belongs to a higher

life. (Of course, there were also instances when the artistic career would be

potentially damaging to one’s reputation if the true name were known.) The

artist would keep his regular name, at any rate, but all his work would be

signed with his art name. (This, of course, would play hell in the SCA in

establishing a reputation of an artisan or craftsman if you were involved in

other areas as well, unless you sign everything in kanji, so it is the same

person, same name; only the reading is different.) These names would often end

with such suffices as ~dô (hall), ~ka (retreat), ~tei (pavilion), ~kaku (tall

building), etc.

Many followers of the Pure Land

Sect, or other followers of Amida Buddha, showed

their attachment to Amida by appending ~a or ~ami to a single kanji

read in the Chinese style in either their given or surname (e.g.; the famed

playwright Zeami, and the artist family of Hon’ami).

Return to Kanji 101